2. Detail of the Last Judgment

Deathmask of a Girl Drowned in Paris---1895

About the forehead only a slight grimacespeaks of something human, something flawed.

The mouth large, open like a kiss.

The eyes tightly closed, as if she were

a saint seeing God in the darkness.

The cheeks hard and smooth, like stone

water has polished for an eternity.

Did someone really live in this face?

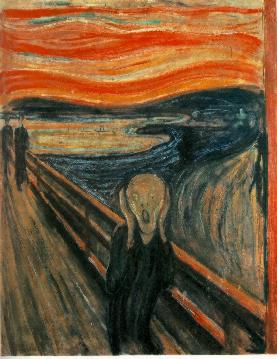

Edvard Munch---The Shriek 1910

Is there no one here to ask:

who is this who has lost his way

among unlistening stars?

All the body is pure sound

bursting from its edges

echoing back merely upon itself.

He has released the undulant world

like a womb.

This is the only shape such terror knows,

all contortion of flesh,

all noise—

helpless as a whisper against eternity.

Paul Delaroche---The Execution of Lady Jane Grey for Charlotte Elena

All are in place: the weeping servant girls

who cannot bear to look, the ministering priest,

the patient executioner with polished blade

ready in hand, the venerable oak block

contrasting strangely with the one-day straw.

And Lady Jane herself, blindfolded, terrified,

her brief seeing in the complicated world

already done, kneels with her best satin gown

drawn to a murderous décolleté.

The artist has delighted in the clash of textures here:

satin and steel, velvet and burnished wood,

straw and the poor girl's length of red-gold hair

so soon to be incarnadined. Another bride to death.

Others pass blithely by this scene, but you, my little one,

bring to it your four year old passionate stare,

an innocence, like hers, confronting death

(which even wise ones can't explain) as by necessity,

and a regard of love to span the blank centuries

hanging suspended where the servants dare not look.

Death on the Battlefield: Photograph from the Spanish Civil War

Beneath his feet, teemingthe earth swoops; above him

the sky is as blue, perhaps, as this one today

powdered by a cloud or smoke. What matter?

Our attention, of course, is riveted in black and white

upon the pure agony held motionless:

his body's helpless loss of grace,

his contorted features, the bit of his head

being blown off—constantly, for all these years.

We wonder if for for a brief moment before

he saw the anonymous killer;

or was he taken, suddenly, from humbler thoughts:

the pleasantness of the morning, a glass of wine

to be drunk that night, an evening with his wife?

What matter? He relinquishes all that

along with his last seeing, his last hearing,

the taste in his mouth, the eternal heaviness of his weapon.

His cause is now the earth.

Attic Stele on a Child's Tomb

Now that earth has recoveredfrom the wound inflicted by her grave,

she will appease the day's blue yearnings

with a journey, her casual eye

pausing in the usual, the well-worn places,

casting about for the flesh of memory.

Out of Chthonic depths she brings a smile

through centuries of youth, through all

the deep imaginings of spring, into

the warmth of stone. There she rests,

waiting in her smile like a kiss.

The Lacemaker Ca 1666

The light as usual enters from her left

To fill the almost empty room;

Her hands, practiced, meticulous, and deft,

Attend the rich laces on her loom.

In detailed miniature she pours her fine

Devotion, soul, and female heart.

Her eyes, like Milton's, someday may go blind

From the long peering of her art.

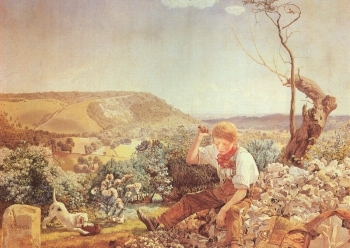

John Brett---The Stonebreaker---1857-58

He is younger even than his morning

spread with such soft, early light,

purpled with miles of distance,

wild-flowered and blue-skyed.

He wonders, bending with his mallet,

are there times when there aren't any hours,

times made of Sunday afternoons,

times made of meadows and wild-flowers?

But today the great rocks have yet to grow little

(as they must), and though the dog would play,

he bends disconsolately to his task,

the consummation of his day.

Behind him, a robin perches on a tree-stump;

before him, like bones haruspically tossed,

the broken knuckles of the stones:

the future where his gaze is lost.

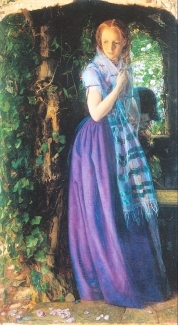

Hughes---April Love---1855-56

She is not one to be taken, some midsummer's

night, under a hedge, but still, in her ivied bower

strewn with a first fall of lilac-colored blossoms,

she requires discretion. While she looks outward to the light,

her lover kneels behind in shadow, as natural

as the green, blossomed background of his furtive kiss.

A kiss of nature. And she yields to it

uncertainly, her hand at first, and what sensations

thrill her we may only guess, as whether she will flee

next moment into the sunlight that strokes

her cheek and hair and arm and the blue folds

of her dress, or turn from us to his soft shadowy

caress.

Gainsborough---Giovanna Baccelli---1782

Gainsborough put her in that abstract land,

Arcadia, and set her dancing to a shepherd's flute

(his timbrel lies nearby), ribboned her dress

with colors of the sky, and strew her path with roses.

But something in her blushing cheeks, and the smile,

delicate and Italianate, on her lips and eyes,

tells that she won't stay framed in Arcady for long.

She is no pale nymph, but a woman whose passion

is for the world of days and weathers, of momentary

musics, roses blowing and blown. For her

mere mortal loves suffice, all preparations and regrets

at which she smiles her sly, sweet, knowing smile.

Sargent---Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose---1885-86

The elements of this painting mesh so well

that there seems little to say, but to remark

Dorothy and Polly lighting lanterns in their garden

in Broadway, in summer, in twilight, innocent.

Surrounding them, to set off their innocence,

lush grass and a full complement of flowers:

“carnation, lily, lily, rose.”

Tall white rubrum lilies tower over the girls

mid clusters of pink and deep red roses, and yellow

carnations scatter palely at their feet. The lanterns

even are like exotic flowers, gold and red, or unlit

coolly blue. But pinning of color to thing

is arbitrary and abstract. The momentary light

is everything to our view. White is never white:

the girls' dresses stream with ochre, green, pale blue,

the light of the lanterns leaps to their hands and faces

redish gold, an echo of the lilies' dangling stamens.

Even the grass shows a range of hue that hardly

can be named with green. The colors merge here

in the harmony of one moment all their own, remaining

when the flowers and girls have faded and are gone.

Horse Dying at his Cart---Andre Kertesz

In the distance, too far to be made out clearly

the dome of a church in soft gray silhouette,

to which, doubtless, this road eventually will lead.

He will not know that time. Suddenly

his work and aches and strength have flown from him.

He lies too helplessly at rest—

no words nor whip will shake him from it.

Now the peasant and his wife must yank the bit

from his teeth, and pull the harness off

with a roughness that knows too well their common fate.

If he is still breathing, they will break his head in

with a stone, and go on arm in arm

bearing up the sky till bearing is no more.

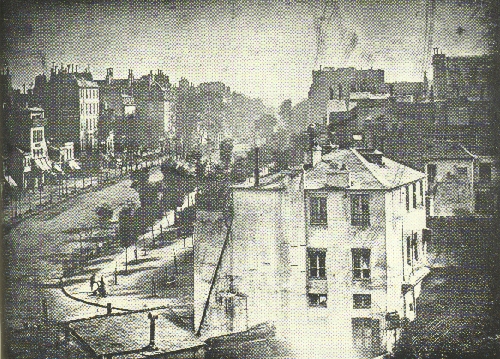

Paris Boulevard by Daguerre---1839

Branches or boughs? There is no telling here.

A sudden wind, perhaps, kindling in the trees,

consumed the season of this boulevard.

The crowd, impatient, intent as always

on the moment, vanished with it.

Only the dark souls of the carriages

on cobblestones emptied of their clamor,

smokeless chimneys, stolid buildings

their windows thrown open to the sun,

and one shadowy figure in profile remain,

mementoes of the invisible alive.

Young Lady Aged 21, Possibly Helena Snakenborg---1569

Over the dry centuries features reappear;

we wonder and are terrified. Helena,

aged twenty one when Shakespeare was but five,

shows off her jeweled dress and ruff and feathered hat;

her red hair, curly and close cropped like a boy's,

exposes the attached lobe of her ringless ear.

A narrow face, high cheekbones, tremulous lips

and questioning, large, doe-like eyes give her

a far away, almost a tentative look as she peers

out of her childhood into the great world of marriage,

courtliness, and death. Four centuries distant,

tremulous too, her double in street clothes looks at her a moment,

searching, like us all, the silenced secret of the past,

and then shied by my presence, moves to another room.