Expressive poets, from the romantic period to our own, have labored under the double threat of belatedness and solipsism. On the one hand, their work can be seen as a struggle (Harold Bloom might term it Oedipal) to establish their identities in the shadows, as it were, of strong and influential precursors. At the same time, expressive poets are more or less constantly in danger of falling into a subjectivity that may prove an impenetrable barrier to their readers, and thus into a kind of voluble silence. Writing poems about paintings and other works of visual art has been one means, both of overcoming such subjectivity and at least side-stepping the issue of literary belatedness. Poetry about art is still, of course, belated, but it enjoys a more reassuring metalinguistic relation with its subject. Poets as disparate as Keats, Rilke, Auden, William Carlos Williams, Pound, and Richard Wilbur have used this approach at one time or another, as we shall see with differing emphases and differing senses of the possibilities of the form.

Remarkable as many of the poems about art have been, it is equally remarkable that there have not been more of them. There are definite limits to this kind of poem. No major poet has made poetry about art his life's work (as, say, certain composers have devoted themselves entirely to Lieder). Many poets have sampled the form, either as a corrective for intense subjectivity or to take the measure of a theme suggested by art, and then drawn back into what one might call the area of life studies. Yet the poems about art are more than just exercises; they include some of the most beautiful poems in the Western tradition. This essay proposes to investigate poetry about art as a distinct sub-genre with its own typical concerns, possibilities, and limitations of expression.

It is worth considering at this point the problem of such poems being, so to speak, at a second remove from experience. What I referred to as the area of life studies is not really as simple as it might seem. In recent years, it has become fairly common to speak of a poem as reading other poems. This is perhaps the essence of Harold Bloom's elaborate theories of belatedness. As George Steiner notes, much of the “charged substance” of Western poetry “is previous poetry: Chaucer lives in Spenser who lives in Dryden who lives in Keats”(22). In a similar vein, Richard Poirier has argued that “the kind of coherencies we should start looking for” in literary study “ought to have less to do with chronology or periods than with habits of reading...and with the way poets ‘read’ one another in the poetry they write”(100-01). This amounts to a view of poetry as metalanguage, an operative form of critical discourse that takes as its object not “the real thing” but a system of signs itself covering “the real thing”. Roland Barthes defines a metalanguage in Elements of Semiology, as “a system whose plane of content is itself constituted by a signifying system”(90). Semiology, of course, recognizes many orders of signs other than language itself, including the visual signs of painting and the visual and plastic signs of sculpture. Poems about art are thus distinguishable from other poems not because they are uniquely metalinguistic but because they take as their objects visual and sometimes plastic significations.

Poems of this kind share a number of defining characteristics. They attempt to mediate, first of all, not natural objects or linguistic objects but works of plastic art, paintings, sculptures, or in the case of Keats a painted vase. Though engagement of such art calls into play a number of senses, the initial stimulation of the poems is primarily visual. Interestly, poems about music, where the auditory sense predominates, are much more rare. Indeed, language has a peculiar difficulty dealing with the experience of music. The attempt to describe sound invariably takes refuge in awkward visual metaphors. (Baudelaire's metaphor of the sea is among the best of these.) Poets seem more interested in and more capable with the music that, “when soft voices die, / Vibrates in the memory” (Shelley, “To —”), or “spirit ditties of no tone” (Keats, “Grecian Urn”), or even the “music” that is really a metaphor for the sounds of nature. Images and story, which the visual arts possess in abundance, come more easily into verse than the relatively abstract emotions, no matter how powerful, suggested by a piece of music.

And images and story provide an anchor in objectivity for the poet's feelings. Yet if a poem about art is to be more than a versified art history lecture, it must somehow get beyond the work of art itself, either by dramatizing the interplay of the poet's feeling with the objective image of the work, or by suggesting some other relation between what is inside and outside of the frame.1 The frame of a painting provides useful limitations on the imagination of the poet (comparable in its way to the limitations of strict form), but what is interesting as poetry is the pull of his imagination against the frame, the tension between a static, objective image and the poet's dynamic, subjective response. Thus, when considering a poem about art, it is usually interesting but not essential to know the work of art itself. The poem provides a concrete linguistic equivalent of the images of the art work, with the important addition of the dimension of time.

The concept of time as it comes into play here is actually somewhat ambiguous. The work of art does not make use of the dimension of actual time, as music and poetry do, though it may imply time in its stilled motion. The poet may play with this implied time, as any apprehender of the work of art is expected to do. Richard Wilbur does this, for instance, in “The Giaour and the Pacha,” based on a painting by Delacroix, by taking up the elements of the painting in time and presenting them as dramatic characters:

The Pacha sank at last upon his knee

And saw his ancient enemy reared high

In mica dust upon a horse of bronze,

The sun carousing in his either eye,

Which of a sudden clouds, and lifts away

the light of day, of triumph;...

* * * * * *

Imbedded in the air, the Giaour stares

And feels the pistol fall beside his knee.

“Is this my anger, and is this the end

Of gaudy sword and jeweled harness, joy

In strength and heat and swiftness, that I must

Now bend, and with a slaughtering shot destroy

The counterpoise of all my force and pride?

These falling hills and piteous mists; O sky,

Come loose the light of fury on this height,

That I may end the chase, and ask not why.” (187)

Shifting from the past tense to the present, and then offering the speculations of a first person speaker (the Giaour), Wilbur suggests a past, present, and future for the painting's figures. The Pacha's killing evokes the moment past, while the Giaour's troubled thoughts at slaughtering “the counterpoise” of his “force and pride” effect the present moment (the moment of the image) and imply the future, into which his regret proposes to last. By providing such thoughts for the Giaour, of course, Wilbur is “reading” Delacroix's image, just as any critic or other viewer might, and expanding the image against the limits of its frame.

Figure 1.1: Delacroix, The Giaour and the Pacha

Keats's “Ode on a Grecian Urn” deals extensively with this other aspect of time. Indeed, Keats plays also with the urn's time, in manner similar to Wilbur's, when he speculates, for instance, about the village that has been left deserted, or toys with the notion of the lovers who cannot consummate their kiss “Though winning near the goal,” but he is ultimately concerned with the urn as a “Cold Pastoral,” depicting the eternal landscapes of Tempe and Arcady. The poem opens with an invitation for the silent urn to speak from its pastoral seclusion outside time to its time-bound perceivers: “What men or gods are these?” The urn, of course, frozen in time and timeless at once, cannot speak for itself, and so Keats takes up one image after another, imaginatively recreating the time of the urn and then contemplating the urn as an object outside time: “Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought / As doth eternity.” Indeed, this teasing out of thought, carefully limited by the images of the urn itself, provides the imaginative body of the poem. The second, third, and fourth stanzas represent the struggle (and play) of Keats's imagination with the silent images of the urn questioned in stanza one. The images provoke various moods in the poet, ranging from celebration of the urn's timeless estate (“Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter”) to a kind of envy of its timelessness (“Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed / Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu”), and finally to melancholy awareness of the urn's Arcadian isolation from the concerns of human beings in time (“little town, thy streets forevermore / Will silent be; and not a soul to tell / Why thou art desolate can e'er return.”). Keats's ultimate judgment of the urn, much debated by the critics, is ambiguously negative. The urn, though “a friend to man,” is still a “Cold Pastoral,” whose speech, as imagined by Keats from the silence of its images, is self-referential, a tautology of its plastic form: “‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,’—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” It is not, of course, all that a human being needs to know, who knows in time. The urn, as a work of art, stands ultimately outside of time, and like Rilke's “Brunnen-Mund” speaks not to us, but murmurs endlessly to itself. Unlike the speaker in whom the voice of a nightingale induces a state between waking and sleeping, the speaker in “Ode on a Grecian Urn” is left distinct and untouched (in a literal sense) by the art object of his meditation.

This is not the case in what is perhaps the second most famous poem (after Keats's “Ode”) about a work of plastic art in the western tradition, Rilke's “Archäischer Torso Apollos.”2 The object of Rilke's meditation is interestingly a fragment, a headless torso that might easily seem simply “entstellt,” or disfigured. Only an effort of the imagination, the poet/viewer's now as well as the sculptor's, can restore its energy. Unlike Keats's urn, whose soul is stillness and silence, Rilke's torso is perceived in terms of energetic movement and communication, its center being not the missing head, the Haupt, but the loins, the place of procreation, that “Mitte, die die Zeugung trug.” The torso is not easily read, however. The “Augenäpfel” of the “unerhörtes Haupt,” which we might expect could be easily picked, read, and made our own, are not available to us, and so we must seek something more strange, the torso's Schauen, its deep gaze, within, which we can only imagine from the remaining suggestion of it. The torso still “glows” with this gaze, but it has been zurückgeschraubt, or turned down like the gas in a candelabra. The signification of the torso, lacunal in itself, must be completed by means of the poet's metalanguage. As in a teleological argument, we are expected to deduce the source of energy from its effects, the “bend of the breast” that “blinds” us, and the “smile” that still runs to the loins. Indeed, as a work of art, the torso is not Arcadian and timeless, but persisting in time, and challenging to us in time. The “translucent plunge” of the shoulders glistens “wie Raubtierfelle,” like the fur of a wild beast. The living energy implicit in the metaphor of the wild beast's fur is now intensified in a second metaphor: the torso bursts out from all its borders “wie ein Stern,” or like the wild flux of fire that envelops a star. The torso, as imaginatively viewed by Rilke, is not a self-enclosed, timeless entity, but something constantly testing and straining at the boundaries of itself. But the torso has this power only on the subjunctive possibility that we see it with Rilke's imaginative intensity. Then, and paradoxically, it sees us without eyes, speaks to us, and unlike Keats's urn, changes us irremediably. “Du mußt dein Leben ändern,” unlike “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” is not self-referential, but aimed at the viewer in the full force of its meaning. The energy of the torso persists in its call on our attention—after this, you can never be the same. In our perceiving it, we bring the torso to life, and at the same time the torso meddles with us, and Rilke's poem dramatizes this experience of art and the energy that mediates the two constituents, viewer and object, of the experience.

Rilke was a poet to whom the ironic stance was utterly foreign. His torso is treated as if it existed on at least equal footing with its perceiver. Beyond the title, there is no suggestion of a creator and his artifice. When we move to a poem like “Musée des Beaux Arts” by W. H. Auden, we encounter a different set of coordinates, a different ordination. Auden insists, first of all, on an explicit aesthetic and ironic distance from the object of his meditation. The poem is about Brueghel's “Fall of Icarus,” but its title

Figure 1.2: Brueghel, The Fall of Icarus

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a windowor just dully walking along...

Auden's free verse lines, with their casual caesuras and prose-like pace (the frequent semi-colons suggest a tumble of afterthoughts), set up and reflect the main point and lesson of the poem, what one might call the banality of suffering, the rather unromantic notion that even “martyrdom must run its course / Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot / Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse / Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.” The painting is used, almost another afterthought, as an exemplum of this phenomenon of human nature. It is thus for Auden one subject among others (the museum, the myth itself, the suggested interlocutors at the museum), united only metalinguistically with these. Auden begins his contemplation of the painting with a quite ordinary and prosy transition: “In Brueghel's Icarus, for instance.” The painting is not locked in a mystery of timelessness, nor does it challenge our own existence with its intensity of being; it is an artifact, to which we may point, and from which we may draw a lesson before continuing on our way. Indeed, the speaker, passing dryly through the museum, is only slightly more observant than the characters in the painting, who continue with whatever work they are doing and do not notice “Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky.” Like the characters in the painting, the speaker's voice is “leisurely” and “calm,” and like the situation of the painting, ironical.

Icarus, of course, is a highly charged, romantic myth of human aspiration, and was never treated by Elizabethans or Romantic poets with anything but high seriousness. Brueghel mitigated the intensity of his subject in a busy painting that shifts the focus from the impulsively romantic Icarus to the common people. Following Brueghel in this, Auden controls the powerful myth with filtering layers (such as his off-hand tone and indirect approach, the device of presenting the museum before the painting) which surround his experience. Part of this is the explicit presentation of the subject painting as a work of art, and even the mention of the artist's name. In this Auden goes beyond Wilbur, who treats the Pacha and Giaour as primary subjects of dramatic immediacy. Auden's Icarus is a secondary subject, whose moment of time stands aesthetically apart from the time of the poem, the speaker's trip through the museum.3

William Carlos Williams writes about Brueghel also, but without the distancing self-awareness of Auden. The typical Williams lyric aims at an ingenuous colloquial simplicity, which the best poems achieve. “The Dance,” about Brueghel's “The Kermess,” is not different from many other of Williams's poems in this respect. Although it explicitly names a painting as its subject,

Figure 1.3: Brueghel, The Kermess

In Brueghel's great picture, The Kermess,

the dancers go round, they go round and

around, the squeal and the blare and the

tweedle of bagpipes, a bugle and fiddles

tipping their bellies (round as the thick-

sided glasses whose wash they impound)

their hips and their bellies off balance

to turn them. Kicking and rolling about

the Fair Grounds, swinging their butts, those

shanks must be sound to bear up under such

rollicking measures, prance as they dance

in Brueghel's great picture, The Kermess.

As usual, Williams is busy breaking the back of the pentameter line, though here the “off balance” verses with their extreme enjambments echo, or reflect, the off balance positions of the dancers in the painting. In fact, the effect of the rhythm is of just such a continually deferred falling as we imagine for the characters of the painting. Williams's rhythms actually create, in a way none of the other poems we have considered do, the motion, and thus the time of the art image being described. In Auden's poem, the speaker's time and the moment of Icarus' fall are aesthetically distinct; in Rilke's poem the torso's presence in time invades and overwhelms that of the speaker; in Keats's poem the urn stands outside the speaker's time; in Wilbur's poem the speaker accepts the time of the painting's characters as a dramatic condition. Williams reinvents the time of the painting. The overall form of “The Dance,” like the dancing it describes, is circular, and thus at once dynamic and static. This also reflects the condition of the painting, where motion is stilled and yet constant motion is suggested. The poem fairly twirls from its first line to its last, which being the same as the first, may be said to begin the poem again, and so on. Williams is not simply transcribing the painting, of course. His imagination is at work, implying the vigorous motion and suggesting “the squeal and the blare and the / tweedle of bagpipes,” a far cry from Keats's “spirit ditties of no tone.” We should remember, however, that the “ditties” of Brueghel's painting are in themselves “of no tone.” The disposition of this poet is to provide them with one. The tone of the poem is one of festive intoxication with the human condition. Beyond the notation that the events described take place in a “picture,” no distinction is made between the world of art and the world of human life. Simply by not recognizing a barrier dividing these worlds, Williams mediates effortlessly between them. Williams's poem would like to disappear in its subject; it can be seen as a metalanguage only in the sense that translation cannot help being at some level a metalanguage.

Ezra Pound, Williams's contemporary and friend, is not nearly so innocent or so comfortable with the border vaguenesses of life and art. The Yeux Glauques section of “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” deals in considerable detail with Burne-Jones's “King Cophetua,” a huge painting that dominates one room of the Tate Gallery in London. Pound's concern, however, is primarily the ironic relation of life to art, specifically the tragically ironic relation of the model Elizabeth Siddal to the characters she portrayed in so many Pre-Raphaelite works.

Foetid Buchanan lifted up his voice

When that faun's head of hers

Became a pastime for

Painters and adulterers.

The Burne-Jones cartons

Have preserved her eyes;

Still, at the Tate, they teach

Cophetua to rhapsodize;

Thin like brook water,

With a vacant gaze.

Poor Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti's wife, who modeled for “The Girlhood of the Virgin Mary”4 as well as the Beggar Maid of “King Cophetua,” and perhaps also the prostitute of the poem “Jenny,” is seen by Pound as hopelessly muddled between life and art. “Questing and passive.... / Bewildered that a world / Showed no surprise / At her last maquero's / Adulteries,” she is drawn to suicide. Most of the poets we have considered are concerned primarily with the relation of a work of art and its perceiver. Pound complicates this relation with consideration of the work's inspirer and progenitor. In other words, he would operate not only on the relation between language and metalanguage but the relation between language and “the real thing”. Indeed, the weight of historical allusion is to this effect. The poem is at once a comment on the misunderstood reception of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. But the painting itself remains in focus. The effect of Elizabeth Siddal's eyes on the perceiver at the Tate (“The thin, clear gaze, the same / Still darts out faunlike from the half-ruin'd face”) leads Pound back through the artifice of the painting to its model and her very human fate. The poem thus imagines and articulates three distinct times: the time of the viewer, the time of the painting, and the time of the painting's model, as it were the mimetic object. Pound's lines are thus suffused with the human mystery of art, the magic by which the living human gesture is taken up, congealed into artistic form, and then released into living human perception. And Pound is acutely aware of the ways the humans—the simple, tragic model or the ironic, compassionate observer—suffer in their contact with the inscrutable timelessness of art itself.

What Roland Barthes claimed of the photograph, that death is its εἶδος, its distinctive form (Camera Lucida 15), is true to some extent of any art representative of the fixed human image, as well of the poems that treat such art as their subject. The people in these paintings are dead and they are going to die (see Camera Lucida 95). The frozen timelessness of Keats's urn mocks at men as much as it befriends them. The invitation to change our lives given by the torso of Apollo is as terrifying in its way as the angels of Duineser Elegien. Icarus' death, amazing in its banal circumstances, dramatizes, more or less, our own. The Pacha and the Giaour, we needn't hesitate to say, are both now in their different afterlives. Even Brueghel's peasants dance over and over a Totentanz, which is after all the dance of life with centuries of dust upon it. Pound senses this too, perhaps even more clearly than the others. The Beggar Maid who still stirs us today is dead Elizabeth Siddal, whose body Rossetti once exhumed in order to retrieve the poems he had impetuously buried with her.

In their differing styles, all poems about art confront this fact of the deathly impenetrability of time. The imaginations of the poets range against it and assault it in different ways—passionate, ironic, innocent—and, indeed, this imaginative stir is the stuff of their poetry, but ultimately they are left with their own timefulness in the presence of images that last longer. Poetry about art constitutes, therefore, a tragic genre, a genre of human limitations from which most poets eventually turn away.

Notes

Works Cited

Copyright © 1989 by Jeffery Triggs. All rights reserved.

This essay proposes to discuss what I shall call the pose of Hamlet with the skull of Yorick as a motif of special significance in poetry and art. My sense of “motif” here is similar to what George Steiner has called a “topology of culture.” Drawing metaphorically on “the branch of mathematics which deals with those relations between points and those fundamental properties of a figure which remain invariant when that figure is bent out of shape,” Steiner argues that there are also such “invariants and constants underlying the manifold shapes of expression in our culture.”1 This notion of cultural topologies grows out of Steiner's sense that culture is to a large degree “the translation and rewording of previous meaning”(415). The motif of the pose of Hamlet involves in its different manifestations all three of Roman Jakobson's categories of translation: intralingual, interlingual, and especially intersemiotic.2

A version of the vanitas or memento mori motif, the pose of Hamlet can be seen in three distinct though interrelated forms: a man or woman contemplating a skull, a man contemplating the head of a statue, and a woman gazing at a mirror. The skull and mirror function interchangeably as truth-tellers and reminders of time and death. The heads of statues, contrasted to the living heads of the observers, are essential skulls. A second division of the motif occurs along religious and secular lines. Saints are reminded of the death of the body by skulls from which they look away. Secular characters, on the other hand, contemplate the objects of vanity directly. A third and possibly a fourth division have to do with traditional and modern instances of the motif and its use in tragedy or comedy. Like the modern use of certain traditional symbols, the modern use of the vanitas motif is characterized by a fluidity which abstraction from the original cultural matrix enables. Tragedy and comedy, of course, involve different ultimate aims, though they may use the same images or language.

I begin, not with Hamlet, but a scene in Dekker's The Honest Whore (Part I), written four years later, where Shakespeare's motif of a man contemplating a skull is reprised to comic effect.3 The Duke of Milan has faked his daughter Infelice's death, rather in the manner of Friar Lawrence, with the intent of preventing her marriage to the melancholy Count Hippolito. Hippolito, having made a “wild” show at Infelice's funeral, remains distracted at the thought of his beloved's death. His friends, who trick him into visiting a brothel, cannot console him. Nor can the “honest whore”, Bellafront, whom he berates at length, and who answers him by falling in love with him and immediately repenting her sinful ways. Sometime later, alone in a room of his house, or rather trying to be (he is continually interrupted), he contemplates suicide as a means of being reunited with his beloved.

The stage directions call for various props suggesting a still life of the memento mori or vanitas variety. On a table Hippolito's servant has placed a skull, a picture of Infelice, a book, and a taper. Hippolito first takes up the picture. Admiring the artist's skill, he turns quickly to a favorite stock subject of the Elizabethans, the “painting” of women:

'Las! now I see,

The reason why fond women love to buy

Adulterate complexion! Here, 't is read:

False colours last after the true be dead.(4.1.45-48)

“Painting” is one of the vanities of man, sustaining as it does, the fiction that man may overcome or at least disguise his fate. As such, it suggests the opposite of the skull or the mirror, both of which tell man the inexorable truth about himself. It is interesting that Dekker links makeup here with the higher art of portraiture. We should remember that until the time of the renaissance, secular portraits were themselves considered a form of vanity. It is not long before Hippolito conjectures that the picture, “a painted board,” is no substitute for the real thing, having “no lap for me to rest upon, / No lip worth tasting”(4.1.56-57). At this point, Hippolito takes up the skull and addresses it (just what the skull is doing there is never made clear):

Perhaps this shrewd pate was mine enemy's:

'Las! say it were; I need not fear him now!

For all his braves, his contumelious breath,

His frowns, though dagger-pointed, all his plot,

Though ne'er so mischievous, his Italian pills,

His quarrels, and that common fence, his law,

See, see, they're all eaten out! Here's not left one:

How clean they're pickt away to the bare bone!

How mad are mortals, then, to rear great names

On tops of swelling houses! or to wear out

Their fingers' ends in dirt, to scrape up gold!

* * * * *

Yet, after all, their gayness looks thus foul.

What fools are men to build a garish tomb,

Only to save the carcase whilst it rots,

To maintain't long in stinking, make good carrion,

But leave no good deeds to preserve them sound!

* * * * *

And must all come to this? fools, wise, all hither?

Must all heads thus at last be laid together?

Draw me my picture then, thou grave neat workman,

After this fashion, not like this; these colours

In time, kissing but air, will be kist off:

But here's a fellow; that which he lays on

Till doomsday alters not complexion.

Death's the best painter then: they that draw shapes,

And live by wicked faces, are but God's apes.

They come but near the life, and there they stay;

This fellow draws life too: his art is fuller,

The pictures which he makes are without colour.(4.1.63-94)

Hippolito is now interrupted again by his servant, who introduces Bellafront, come once more to woo Hippolito, and the comedy moves on its way.

Taken in its rather gratuitous context, Dekker's scene reads like a hilarious parody of Hamlet, as well as other Shakespearean plays (“What fools these mortals be...”). But parody, of course, is one indirection by which we may find direction out. Hippolito's rather overwrought soliloquy takes up and plays, for all a knowing audience knew they were worth, the basic themes of Hamlet's address to Yorick's skull. The motif of a man holding up and addressing a skull was irresistible material to Dekker. The theme of memento mori, here in a comically painless form, is perhaps most obvious: “And must all come to this?” All life, surely, is as brief as Hippolito's taper. But Dekker presents this theme, more pellucidly than Shakespeare, as being linked to the theme of art and its presumed conferment of a kind of provisional immortality. This is suggested in a number of ways: by the still life setting of the stage props, by the portrait of Infelice, by the introduction of the “painting” motif (an art through which we disguise our mortality a while), and finally by the consideration of death as an artist, “the best painter.” The skull, then, is a supreme work of art, challenging with its permanence our own transient existence. Fools and wise, we read in it, as in a mirror, the truth about ourselves. And as a work of art, it overcomes our mortal weakness of being locked in the limited perspective of time. The skull, of course, represents the past, but Hippolito, a creature of the present, reads in it not merely the past, but the future as well: he, too, will come to this. The skull, therefore, involves past, present, and future in a continuum of experience (which may be predicated also of enduring works of art), testing the timeful limitations of the human imagination.

As I suggested above, the interwoven themes of mortality and art are present also in Shakespeare's use of the motif in Hamlet, and as we shall see in a number of diverse works in the European tradition that draw their strength from this motif as well. I have begun with Dekker rather than Shakespeare because the motif in Shakespeare is more thoroughly subjugated to his dramatic purpose, and therefore less obvious in itself. But it is audible even in his more subtle application.

The graveyard scene has long been recognized as one of the most significant in Hamlet. As Maynard Mack suggests, “here, in its ultimate symbol, [Hamlet] confronts, recognizes, and accepts the condition of being man.”4 The scene provides us with “the crucial evidence of Hamlet's new frame of mind”(Mack 62), which will enable him, finally, to engage in the “contest of mighty opposites”(Mack 63) awaiting him at court. Cast in a sober prose rather than the heated verse of the earlier soliloquies, the scene objectifies Hamlet's resignation to the human condition through the vanitas motif of a man holding a skull.5 Hamlet and Horatio watch as the grave digger throws up one skull after another. At first Hamlet responds with wittily ingenuous questions:

There's another. Why may not that be the skull of a lawyer? Where be his quiddities now, his quillities, his cases, his tenures, and his tricks? Why does he suffer this mad knave now to knock him about the sconce with a dirty shovel, and will not tell him of his action of battery?(5.1.91-96)

The focus of these questions is the absence of wonted action and volition; life lost is suggested by the loss of the power to will and speak. “That skull had a tongue in it, and could sing once”(5.1.71-72). The meditation is generalized at first, but takes on a horrible particularity when Hamlet is informed that one of the skulls belonged to Yorick, a person of his acquaintance. He now takes up the skull:

Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio, a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy. He hath borne me on his back a thousand times. And now how abhorred in my imagination it is! My gorge rises at it. Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft. Where be your gibes now? Your gambols, your songs, your flashes of merriment that were wont to set the table on a roar? Not one now to mock your own grinning? Quite chapfall'n? Now get you to my lady's chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favor she must come. Make her laugh at that.(5.1.172-83)

Like Hippolito's speech, Hamlet's turns also on painting (there is a rather chilling echo here of his earlier upbraiding of Ophelia, whose death occasions the scene), and thus on the futility of human art, indeed all human endeavor, before death. Death, for Hamlet too, is the greatest and most ironic painter. Wit, songs, and makeup, jester, queen, or world conqueror, all end alike in the silent verity of the skull. “To what base uses,” Hamlet continues, “may we return, Horatio! Why may not imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander till 'a find it stopping a bunghole”(5.1.190-93).

In The Third Voice, Denis Donoghue makes a useful distinction between “the unit of poetic composition,” which “is necessarily verbal,” and the situational unit of theatrical composition, which

is not encompassed within the verbal realm. If one isolates a moment from the thousands of contiguous moments in a play, one should regard as the unit of theatrical composition everything that is happening at that moment, simultaneously apprehended. Words are being spoken, gestures are being made, the plot is pressing forward, a visual image is being conveyed on the stage itself.6

To consider the graveyard scene in Hamlet in this light is to be aware most powerfully of the visual image of a man gazing at a skull he holds in his hand. Our method of interpretation, therefore, is not simply verbal or linguistic, but emblematic. Like Hippolito, Hamlet gazes at the skull as into a mirror, showing him at once past and future, and signifying at once verity and vanity, that he too must come to this favor. The motif Hamlet enacts functions, of course, as part of the plot which is pressing forward, but at the same time it establishes emblematic connections with other works of art that make use of this motif as part of the human way of knowing.

The contemplation of a skull is a common motif in paintings of the period. Often a saint is depicted with a skull, suggesting his awareness of the vanity of human endeavor. Cavarozzi's painting of St. Jerome, for instance, portrays the scholarly and ascetic Jerome at his writing table watched over by a crucifix and two angels.7 On his table are several old books, religious beads, a sand-glass, and in the foreground a skull facing outward. These images suggest at once the bearded saint's holiness and his humanity. The crucifix, the angels, and the beads guide and guard him, or rather his immortal part. The books represent his characteristic erudition, the toil of human wisdom. The sand-glass and the skull, however, are symbols of human vanity, the glass reminding us of the time-bound human condition and the skull reminding us of death. That Jerome keeps these articles on his desk suggests also his own awareness of time and death. The skull, placed on a book and facing outward, echoes by its position in the painting the bald head of the saint. Positioned between the head of Jerome and the skull, the glass serves to conjoin the two; this head, given the passage of time, will become that skull. Even the light, lingering on the two foreheads, implies their identity. A significant difference between the image in Cavarozzi's painting and the image in Hamlet is that, unlike Hamlet, Jerome does not contemplate the skull directly. As a tragic hero, “crawling between earth and heaven,” Hamlet is very much the ordinary mortal with little “relish of salvation” in him. For Hamlet, as I have noted, the skull is in effect a mirror of his humanity, into which he gazes with all possible scrutiny. Jerome, on the other hand, pursues his characteristic work, which involves primarily the contemplation of divinity (one of his open books contains what might be a pieta). He is aware of the impending death of his body, as the skull suggests, but this affects a part of his consciousness only and by implication. The painting, though it involves memento mori, does not dwell on this, but celebrates Jerome's human activity.

Similarly, Ribera's portrait of St. Francis depicts the saint holding a skull in his hands but gazing upward at the vision approaching him from heaven.8 Already marked with stigmata (a hole in his garment and a mark on one hand reveal this), Francis seems ready at this moment to leave behind the travail of his body and to become one with Christ in mind and heart. The position of the skull in Francis's hands suggests, however, that in the moments before the heavenly vision he was contemplating the skull directly, directly contemplating the vanity of earthly life very much in the manner of Hamlet. Interestingly, the fissures in the skull, which form a sort of rough cross, echo the stitchings of the saint's rag garment. The skull and the garment of rags, taken together, suggest the earthly trappings of the soul, from which it would escape. The cross on the skull reminds us that even Jesus' human body could not avoid the experience of death. If the skull is a mirror of Saint Francis's human life, however, it is a mirror from which he looks away toward salvation. Vanitas is merely one constituent of the religious experience being presented.

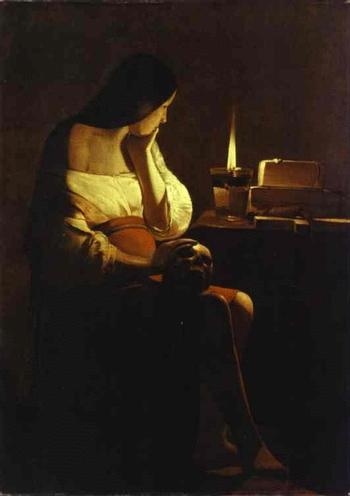

Georges de La Tour, in his painting, Magdalen with the Lamp, also makes use of the skull as an image of vanitas.9 The Magdalen sits at a table holding a skull on her knee. On the table is another still-life setting: a glass oil lamp (the painting's only light source), two books, a scourge, and a wooden cross. Her right hand rests on the forehead of the skull, while her left hand supports her chin in a gesture of melancholy meditation. Once again, the saint's meditation is not directly on the skull; she gazes away from it, as it were, through the lamp's tall flame into the darkness of the background. Her thoughts are on the salvation possible only in another world. The light, however, flows from her hand to the skull, joining them in effect, while the position of her left forearm connects the skull with her own head. The end of earthly life, as the skull, the scourge, and indeed the cross remind us, is death. As T. Bertin-Mourot has pointed out, “the theme of the Magdalen in meditation is a synthesis of ... Melancholy and Vanity.... La Tour's is the mystic feeling of this poignant dialogue between the penitent and God, in the contemplation of Death.”10 La Tour's mysticism, therefore, asks us to go beyond Hamlet's human meditation. Hamlet, contemplating death as the certain end of all human life, throws down his skull and turns to act out the life remaining him. The Magdalen, like the other saints discussed in this context, looks through her death towards a salvation made possible only by the human oblivion of the skull. The mystic, reminded of death, is essentially uninterested (certainly the scourge suggests this) in the life she is to leave behind.

In secular works, however, the implications of the vanitas motif are more chilling. As I have suggested above, the skull is effectively a mirror, revealing to the subject his future at the same time that it reveals the past. A literal mirror is also commonly used in exercising the motif. Titian uses both a skull and a mirror as images of vanitas. There are two similar versions of the Magdalen subject that depict the saint gazing upward toward heaven, while an open book lies before her on a skull. In both versions a black ribbon drapes the skull, suggestive of the human vanity she is leaving behind. Other Titian vanitas paintings make use of mirrors. A painting attributed to Titian and entitled simply Vanitas shows a woman at her toilette gazing into a mirror held aloft by Cupid.11 This painting is quite similar in theme and composition to the famous Toilette of Venus. 12 Here two cupidons assist the goddess, one holding the mirror and the other a garland for her hair. Venus wears pearls in her hair, earrings, costly bracelets and rings, and (partially) a rich robe of fur and gold embroidery. Gazing at the mirror, however, she sees not her own youthful face and body, but those of an old woman. In Vanitas too, the image in the mirror, though here the difference is not so striking, appears to be that of an older woman. The suggestion of both paintings is that old age and of course death are the favors to which all human beauty must come. Interestingly, though his subject is a Venus, Titian ignores the traditional ascription to the goddess of eternal youth. This suggests of course a devaluation of the Greek myth in a Christian century; the goddess is depicted in effect as a secular figure, and her vanity proposes itself therefore as something essentially human. Whether we wrap ourselves in costly furs and jewels, or “rear great names / On tops of swelling houses,” or indeed “paint an inch thick,” this is the end of human beauty, love, and life. Like the skulls in Hamlet and The Honest Whore, Titian's mirrors suggest also the vanity of art and what E.R. Dodds once called “the offensive and incomprehensible bondage of time and space.”13 The images in the mirrors are framed, or delimited in space as if they were works of art. This implies, of course, the reasonable but limited confines of human activity. And the images in the mirrors, like the skulls, suggest an inescapable future time as well as the past (for do we not become in the future like those human Yoricks we once knew?). The vanitas motif, in its secular form, involves a human confrontation with the boundaries, in time and space, of human endeavor. The truth-telling skulls and mirrors, from which, mere mortals, we cannot take our gaze, remind us forcefully of these limits.

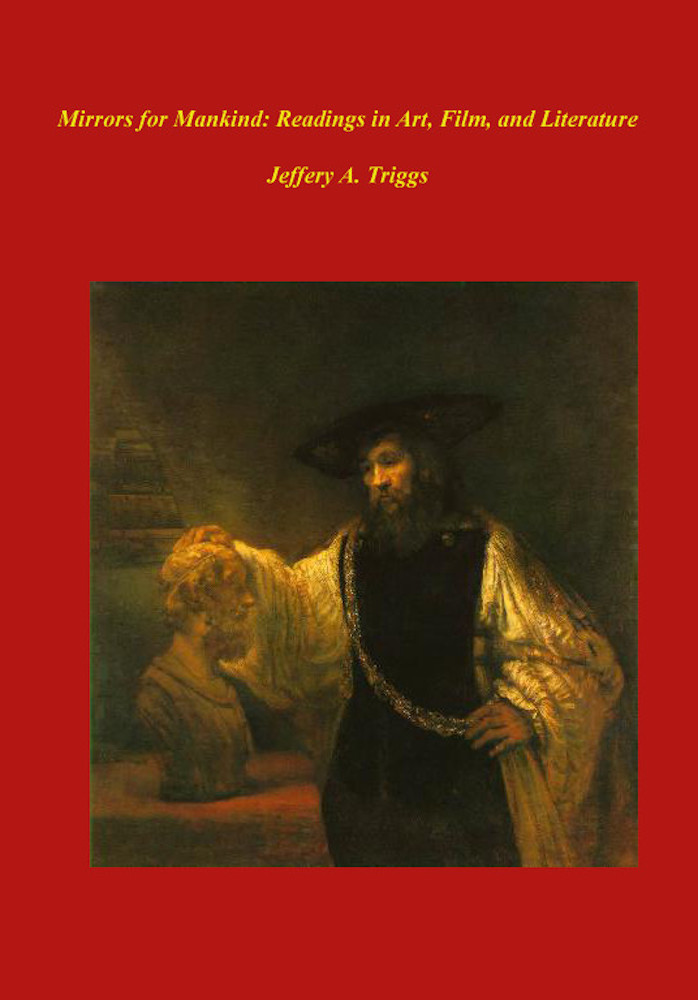

Before proceeding to some typical modern instances of the vanitas motif, I will consider one more version from the seventeenth century, Rembrandt's moving image of Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer. 14 Dating from 1653, a time when Rembrandt's later style was beginning to be noticeable, the painting depicts a contemporary looking, bearded Aristotle gazing at a bearded sculpture of the fabled epic poet. Aristotle's left hand rests on his hip; his right hand is extended and rests on the head of the sculpture. The light passes from the sculpted head to Aristotle's face along the extended arm, which is clothed in a voluminous white sleeve. In effect this joins the two heads, as does the similarity of their beards. Rembrandt's image, while different from either the skull or the mirror images we have considered, combines in essence the elements of the vanitas motif present in both of them. Like the skull, the sculpted head suggests a lifeless image from the past. It is an essential skull, and in gazing at it, Aristotle confronts the vanity of even the most brilliant human endeavor. This head had a tongue in it once and could sing. It represents also Aristotle's future, for at some future time his physical being will be similarly silent; like his famous pupil, Alexander, Aristotle may find a new calling stopping a bung hole. And Rembrandt's painting suggests quite forcefully that the sculpted head is a kind of mirror. Both men are bearded and similarly featured. The sculpted head, however, speaks of death, and carries with it the burden of the past, which is, of course, the burden that the future must learn to bear. The anachronism of Aristotle's contemporary dress suggests that Rembrandt had in mind a more universal relation of living man to dead than simply the special subject of the two Greek thinkers. The future, the time of his own death, which Aristotle sees in an image of the past, is Rembrandt's time, and by extension our own. The anachronistic dress, along with the vanitas motif itself, scorns the artificial distinctions of time, which is actually a continuum imprisoning us all. That the sculpture is palpably a human work of art introduces more obviously than we have seen elsewhere the notion of art as a provisional confrontation with mortality which ultimately must confirm it. Like Hamlet, therefore, and unlike the saints, Aristotle confronts and—as his sober look suggests—accepts his own mortality.

The vanitas motif, as I have discussed it so far, might seem simply a phenomenon of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Indeed, all the works used here to round out the theme were produced between 1550 (the earliest ascribable date for Titian's Toilette of Venus) and 1653 (the date of Rembrandt's painting). Shakespeare's Hamlet, which was most probably written in 1600, appeared roughly in the middle of this period. The vanitas motif is an important and well-known ingredient of the Zeitgeist under which these artists worked. What I shall now try to demonstrate is that this motif is also important, though less formally worked out, in our own century. It is certainly visible among the fragments our artists have used to shore against their ruins, and if anything its grim message is grimmer still in a century when saints are mostly silent and religion is steadily on the wane.

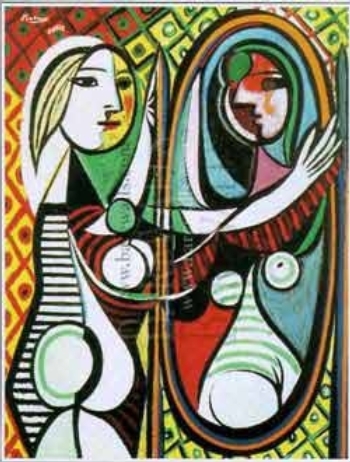

One of Picasso's most fascinating paintings is the Girl before a Mirror of 1932, now at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.15 Like many of Picasso's paintings of this period, it makes use of multiple images to suggest movement or the passing of time in a medium whose traditional convention was of temporal stillness. The girl stands before what might be a cheval-glass at once in profile and facing forward. The left profile of her face rests in an oval, full-face outline, in which the features of the right side are extended in a different color. A similar ambiguity attends the depiction of her legs and belly; there may be one or two legs, depending on how one views a line running down the middle of the figure, while a circular shape may suggest the frontal view of the belly or an interior image of the womb. From the stylized emphasis on her breasts and belly, it appears that she may be pregnant. Her arms are extended in the act of adjusting the glass, and one arm, therefore, interacts in terms of color and design, with the mirror image. As Alfred Barr notes, there is an “intricate metamorphosis of the girl's figure—‘simultaneously clothed, nude and x-rayed’—and its image in the mirror.”16 This metamorphosis expresses itself in terms of oppositions of color and design which suggest the opposition of life and death. As in Titian's mirror paintings, the mirror image here both reflects the figure and comments on the figure through its variation. The most obvious variation is that of color. The stripes suggesting the girl's clothing are differently located in the mirror; what is nude is clothed in the mirror. The colors in the mirror are generally much darker than those of the girl herself. Her hair, as well as part of her face, is yellow and is set in what seems to be a white radiance, shaped almost like a bridal veil or halo. The face in the mirror, on the other hand, is composed of a silvery gray marked with reds, purples, green, and black, which flows into a heavy outline; the hair is green, outlined, and surrounded by what seems to be a bluish veil. Where the girl's face and hair suggest the sun and daylight, the mirror's face suggests the moon and night. Its color, grayish and blemished as it were with purple, creates a skull-like image. This is reinforced by the fact that while an eye is drawn in the girl's profile face, the face in the mirror has only a dark shape suggesting an empty eye-socket. Even the long oval of the cheval-glass has about it, in Nabokov's phrase, “the encroaching air of a coffin.” This deathly air is enhanced by the stylized shape of the girl's neck, which is drawn as an Egyptian pyramid. Thus the striped clothing of the girl in the mirror may suggest the wrappings of a mummy.

The major opposition of the painting, very much in the vanitas tradition, is of life and death. Picasso combines the vanitas images of the mirror and the skull and involves the related theme of art (the cheval-glass could also seem a portrait on an easel, a painting within a painting). But Picasso's use of the vanitas motif is modern in sensibility as well as style. The fact that the girl is seen both in profile and in full face suggests that she is at once contemplating the image in the mirror and looking away from it. Unlike a saint, however, she does not look away toward her own salvation, but turns toward us. Modern human kind, as Eliot reminds us, cannot bear very much reality. Her memento mori is thus ours also in a direct and uneasy way. Her seeming pregnancy, suggestive of the human life cycle and the human urge to continue the chain of life, is still involved in the imprisoning continuum of time. For the modern artist, Hamlet's mortal gaze is more familiar than St. Francis's or the Magdalen's.

Eliot himself includes a “Girl before a Mirror” scene in the “Game of Chess” section of The Wasteland. 17 This is, of course, the famous parody of Shakespeare's description of Cleopatra's barge. The woman with bad nerves sits before her vanity combing her hair: “Under the firelight, under the brush, her hair / Spread out in fiery points / Glowed into words, then would be savagely still”(lines 108-10). As Eliot's many allusions suggest, this woman may be taken as a modern and ironic composite of a number of death-marked women from history and myth: Cleopatra, Dido, Eve, and Philomela. All of them are unlucky in love, and in this respect the woman with bad nerves certainly belongs in their company. The comparisons are ironic, however, because where Cleopatra and the others have acted greatly, as it were, have given all for love, the modern woman remains simply frustrated, another of the “uncommitted ones” who populate the “Limbo” of the modern world. Unwilling to risk “the awful daring of a moment's surrender,” she glows into empty words that suggest merely the breakdown of communication with her lover:

“What is that noise?”

The wind under the door.

“What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?”

Nothing again nothing.

“Do

“You know nothing? Do you see nothing? Do you remember

“Nothing?”

I remember

Those are pearls that were his eyes.

“Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?”(117-26)

What the lover remembers, via Ariel's song, is the drowned Phoenician Sailor, who, as we later learn, “was once handsome and tall as you”(321). This thought is literally, therefore, a memento mori. But as the woman's response implies, they are themselves already among the living dead, neither truly alive nor dead, and as the repeated “nothings” of the passage suggest, essentially empty. Her identity, of course, is blurred with those of the dead queens; her future may be read in their past. Indeed, hers is in effect Hamlet's quandary on confronting Yorick's skull. The setting of the scene reinforces my sense of it as a modern reworking of the vanitas motif:

The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

Glowed on the marble, where the glass

Held up by standards wrought with fruited vines

From which a golden cupidon peeped out

(Another hid his eyes behind his wing)

Doubled the flames of sevenbranched candelabra

Reflecting light upon the table as

The glitter of her jewels rose to meet it,

From satin cases poured in rich profusion...(77-85)

What we have here, cupidons, jewels, and all, is the pose of Titian's Toilette of Venus. This mirror, however, tells the woman not merely of time and death, but of her own emptiness and living death (the mirror is described as reflecting the objects of the room, but interestingly not her image). The vanitas motif, as Eliot invokes it, echoes the central condition of The Wasteland.

Something more akin to Rembrandt's use of the motif occurs in the Mythistorema sequence of George Seferis.18 As the title suggests, these poems are concerned with myth, history, and story, and attempt to express, as Seferis himself puts it, “circumstances that are as independent from myself as the characters in a novel”(261). One of the major concerns is clearly the burden of the past as represented by myth, history, and story. The third poem of the sequence expresses this burden through the image of a man holding the head of a statue in his hands:

I woke with this marble head in my hands;

it exhausts my elbows and I don't know where to put it down.

It was falling into the dream as I was coming out of the dream

so our life became one and it will be very difficult for it

to separate again.

I look at the eyes: neither open nor closed

I speak to the mouth which keeps trying to speak

I hold the cheeks which have broken through the skin

I haven't got any more strength.

My hands disappear and come toward me

mutilated. (5)

The speaker here is very much in the pose of Hamlet: a living man confronting the image of the past and finding in it his own identity (“so our life became one”). The sculpted head, as in Rembrandt's painting, suggests an essential skull with eyes “neither open nor closed” and cheeks breaking through the skin. It “keeps trying to speak,” but it is locked in the silence of the past. The speaker senses and would maintain a connection with this past, but the effort for the living man is exhausting, indeed, mutilating. The world of the dead, of history, is a presence which must be confronted and remembered. In part because of this, it threatens to overwhelm the living person. He does not know where to put the statue down and resume his life; “it will be very difficult for it to separate again.” Though it proposes itself as a waking experience, the poem is clearly nightmarish, an experience of life in the grip of time and death. It suggests no saintly escape from the condition of mortality, nor even Hamlet's return, after confronting death, to the work of living. The body's surreal dismemberment in the final lines argues rather that the self is bound to and lost in the past. Like the other moderns, Seferis's vanitas experience reverberates in a void of lost values.

I began with an example from comedy, and I return finally to a famous comedy of the twentieth century, Hugo von Hofmannsthal's Der Rosenkavalier. 19 Near the end of the first act of Der Rosenkavalier, Hofmannsthal interrupts the opera's merriment with a scene replicating Titian's image from Toilette of Venus. Having set in motion a comic plot that will end in the loss of her youthful lover, Octavian, the Marschallin is left alone for some minutes in her boudoir. The thought of the buffoon, Baron Ochs, taking a young bride disturbs her by reminding her of her own youth and marriage. Taking up a hand mirror, she gazes into it and meditates:

Wo ist die jetzt? Ja,

such' dir den Schnee vom vergangenen Jahr!

Das sag' ich so:

Aber wie kann das wirklich sein,

daß ich die kleine Resi war

und daß ich auch einmal die alte Frau sein werd.

Die alte Frau, die alte Marschallin!

“Siegst es, da geht die alte Fürstin Resi!”

Wie kann des das geschehen?

Wie macht denn das der liebe Gott?

Wo ich doch immer die gleiche bin.

Und wenn er's schon so machen muß,

warum laßt er mich zuschauen dabei

mit gar so klarem Sinn? Warum versteckt er's nicht vor mir?

Das alles ist geheim, so viel geheim.

Und man ist dazu da, daß man's ertragt.

Und in dem “Wie”

da liegt der ganze Unterschied— (Page 42)

(Where is she now? Yes, / seek out the snows of yesteryear! / That I can say: / But how can it really be / that I was little Resi / and that also one day I will become an old woman. / The old woman, the old wife of the Fieldmarshal! / “Look, there goes the old Princess Resi!” / How can that happen? / How can the dear Lord let it be? / Yet I am always the same. / And if He must do it like this, / why does He allow me to look on / with such clear senses? Why doesn't He hide it from me? / All this is mysterious, so very mysterious. / And one is here but to bear it all. / And in the “How” / there's the whole difference—)

Whereas in Titian's painting a young woman looks in a mirror and sees the image of an older woman, the Marschallin is actually an older woman and presumably sees a proper likeness of herself. On a psychological level, however, she does not feel like an older woman. Her sense of self is still that of the young Resi, and therefore the image in the mirror is strange and shocking to her. The “I”, who is “immer die gleiche,” sees a different, older self in the mirror, one clearly subject to the ravages of time. The mirror shows her a future that on a psychological level she did not know had already happened, and the passing of time, of course, threatens to continue. She feels herself slipping irrevocably into the past. Hofmannsthal's image—and it involves here words, gesture, the stage setting, and indeed the gorgeous music of Richard Strauss—presents the vanitas motif in the fullness of its lineaments. The reference to Villon's famous poem about the fading of earthly beauty merely deepens the aura of this tradition. What is more modern here, though it bears indeed a key relationship to the mood of Hamlet, is the questioning of the God who would subject human beings to such a painful consciousness of their fate. A secular character, the Marschallin does not look away in the manner of a saint toward mystical salvation, but concentrates like Hamlet on her own ageing and approaching death. But like Hamlet also, she turns stoically to the business of enduring life, the graceful “how” of things suffering the imprisonment of time, which, as she puts it, makes all the difference.

Comedy may remind us of death, and often forcefully, but its ultimate motive is the celebration of life as it is lived and passed on in the chain of time to the ever changing young. It recognizes the continuum of time as something neither to overcome nor to mourn, but to celebrate: a continuity in flux. This is the mystery that the Marschallin, like Hamlet in his own way, recognizes and accepts. When Octavian returns at the end of the first act, he notices but does not understand her sober mood, and she attempts to interpret it herself:

Die Zeit, die ist ein sonderbar Ding.

Wenn man so hinlebt, ist sie rein gar nichts.

Aber dann auf einmal, da spürt man nichts als sie.

Sie ist um uns herum, sie ist auch in uns drinnen.

In den Gesichtern rieselt sie,

im Spiegel da rieselt sie,

in meinen Schläfen fließt sie.

* * * * * *

Manchmal steh' ich auf mitten in der Nacht

und laß die Uhren alle, alle stehn.

Allein man muß sich auch vor ihr nicht fürchten.

Auch sie ist ein Geschöpf des Vaters, der uns alle

erschaffen hat. (46)

(Time is an odd, curious thing. / When one just lives, it seems like nothing. / Then suddenly one senses nothing else. / It is around us and inside us too. / It trickles in faces, / it trickles in mirrors, / it flows in my temples. / ... / Sometimes in the middle of the night I rise / and make the clocks, yes all of them, stand still. / But also one must not fear time. / It, too, is a creation of the Father who created us all.)

Secular man may be, in Matthew Arnold's phrase, a “chafing prisoner of time,” or he may be an accepting prisoner of time. With a rather touching naivete, the Marschallin makes her case for acceptance. For her, as for the Hamlet who came to see a “special providence in the fall of a sparrow,” the vanitas experience ends in a kind of humility before death and life. The confrontation with time as it flows in mirrors, in statues, or indeed the temples of skulls is a spiritual preparation for the act of living one's limited days.

Notes

Bibliography Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

Copyright © 1990 by Jeffery Triggs. All rights reserved. This essay first appeared in The New Orleans Review 17.3 (Fall 1990): 71-79.

It seems almost odd that a poet as remote, historically, linguistically, and philosophically, as Dante should maintain so pervasive an influence on modern poetry in English, by which we may comprehend the work of romantic, modernist, and contemporary poets. And yet it is easily demonstrable that Dante, a poet with medieval religious beliefs, an elaborately allegorical method, and an Italian system of versification difficult to transpose into English, has been an intimate and profound influence on poets as diverse as Shelley, Dante Rossetti, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Allen Tate, James Merrill, and Wendell Berry. Indeed, Eliot went so far as to recommend Dante as a “universal school of style” (228), a better model for English poets than such native luminaries as Shakespeare and Milton. The nature of Dante's actual influence varies from case to case, and ranges from attempts at “Englishing” terza rima to imitations of the grand structure of the Commedia. In the case of poets like Eliot and Tate, it may extend even to religious admiration, emulation, or attempted revival. The focus of this essay, however, will be on a narrower, and more strategic form of emulation: the recurrence in modern poetry of the motif of meeting and conversing with the dead.

There are a number of reasons that this motif should prove so congenial to the modern sensibility in spite of its allegorical associations.1 For one thing, it provides what one might call an “objective correlative” for the exploration of the unconscious mind, which since the time of the romantics, for good or ill, has been perhaps the central endeavor of poetry. Lancelot Whyte has argued in The Unconscious Before Freud for the centrality of the unconscious in the modern era:

faith, if it bears any relation to the natural world, implies faith in the unconscious. If there is a God, he must speak there; if there is a healing power, it must operate there; if there is a principle of ordering in the organic realm, its most powerful manifestation must be found there. (7)

In poetry, as M.L. Abrams has shown, this habit of mind gave rise to “expressive form” (The Mirror and the Lamp), a revolutionary and pervading sense of poetry as the sincere expression of feeling. The interest of modern poets in the Dantean motif of meeting the dead is thus characteristically psychological, and represents a psychological reinterpretation of Dante's practice, analogous perhaps to the many “expressive” reinterpretations of Shakespeare in the nineteenth century. Whereas in Dante the meeting with the dead is at once literal and allegorical, in modern poets it is suggestive in terms of personal symbolism, a metaphor of the journey into the self.

Significantly, the modern poets generally offer some psychological explanation for their visions, suggestive of intercourse with the unconscious. Shelley's Dantean tour de force, “The Triumph of Life,” is presented, for instance, as a “trance” or “waking dream,” during the course of which he meets with his own counterpart to Dante's Virgil in the figure of Rousseau. Rossetti's “Willowwood” sonnets suggest a dream in which he sees his dead wife and muse, Elizabeth Siddal. Even Eliot's confrontation with the “familiar compound ghost” after an air raid in London is given the quality of a dream or hallucination. And more recently, in “The Buried Lake,” Allen Tate presents a dream-like visit to the underworld. For the modern poets, the psychological aptness of these situations takes precedence over any allegorical function. Their significance, therefore, is not publically accessible, as in Dante, but must be construed in terms which are essentially interior and personal.

Shelley's “Triumph of Life,” left unfinished at his death, recounts in over five hundred lines of terza rima his vision of a wild throng of people being driven before a chariot in which an allegorical figure, or “Shape” of Life sits in Roman-style triumph.2 The throng Shelley witnesses, “Numerous as gnats upon the evening gleam” (line 46), is representative (one might say representative in their misery) of all the stages of life: “Old age & youth, manhood & infancy, / Mixed in one mighty torrent did appear” (52-53). Sexual love is suggested, in uncharacteristically dark and futile terms, by an orgiastic dance of “Maidens & youths” who “fling their wild arms in the air / As their feet twinkle; they recede, and now / Bending within each other's atmosphere / Kindle invisibly; and as they glow / Like moths by light attracted & repelled, / Oft to new bright destruction come and go” (149-54). One by one, they fall exhausted and “senseless” (160) in the path of the chariot, and their place is taken up, in a grotesque parody by “Old men, and women foully disarrayed” who “Shake their grey hair in the insulting wind, / Limp in the dance & strain with limbs decayed / To reach the car of light which leaves them still / Farther behind & deeper in the shade” (165-69). Shelley's final conception of sexual love, as the ending of the generally exultant “Epipsychidion” also suggests, is a pessimistic one, emphasizing futility and betrayal. Harold Bloom has argued that although “the tone of Shelley's last poem is derived from Dante's Purgatorio,... the events and atmosphere of The Triumph of Life have more in common with the Inferno” (xl). This might have been different had Shelley lived to complete the poem, but the fragment as it stands offers a vision of unrelieved darkness, a dying modern man's vision of last things.

This general tone of bleakness is even more conspicuous in the Dantean center of the poem, the meeting with Rousseau, which even T.S. Eliot admired.3 Harold Bloom, a more sympathetic critic, calls it “the highest act of Shelley's imagination in the poem” (xli). Rousseau is quite obviously to Shelley what Virgil, the figure of Reason in the “Inferno” and Purgatorio,” is to Dante, the dead “master” and guide, though we may infer that here Shelley will be guided not so much by Reason as by Feeling. Indeed, Rousseau, in a rather melodramatic fashion appropriate to his role as the archetypical romantic, shocks the poet with his sudden appearance:

Struck to the heart by this sad pageantry,

Half to myself I said, ‘And what is this?Whose shape is that within the car? & why’—

I would have added—‘is all here amiss?’But a voice answered .. ‘Life’ ... I turned & knew

(O Heaven have mercy on such wretchedness!)That what I thought was an old root which grew

To strange distortion out of the hill sideWas indeed one of that deluded crew,

And that the grass which methought hung so wideAnd white, was but his thin discoloured hair,

And that the holes it vainly sought to hideWere or had been eyes. (176-88)

Rousseau is characteristically defiant, claiming that in spirit he “still disdains” to wear his earthly “disguise,” but he is nonetheless condemned with the others “chained to the car” of Life, “The Wise, / The great, the unforgotten: they who wore / Mitres & helms & crowns, or wreathes of light” (205, 208-10). Upon questioning, he reveals some of these, including Napoleon, who “sought to win / The world, and lost all it did contain / Of greatness” (217-19), and “those spoilers spoiled, Voltaire, / Frederic, & Kant, Catherine, & Leopold, / Chained hoary anarchs, demagogue & sage” (235-37). Indeed, almost all men, the great only more conspicuously than the mean, stand condemned, “For in the battle Life & they did wage / She remained conqueror” (239-40). Rousseau himself claims to have been undone “By my own heart alone” (241). As Marius Bewley has noted, “in this poem self-betrayal appears to be almost universal” (870). Jesus and Socrates (and interestingly not his disciple Plato) are virtually alone in escaping conquest by Life because of the peculiar honesty and intensity of their visions.4

What it is exactly that vitiates the others, and by implication Shelley himself, is less certain, but seems to be a matter of impurity of imagination, the one power, according to Bloom's reading, “capable of redeeming life” (xlii). Rousseau's first sentence suggests the importance of withholding one's inner self from the seductive attractions of earthly life: “‘If thou canst forbear / To join the dance, which I had well forborne.’ / Said the grim Feature, of my thought aware, / ‘I will now tell that which to this deep scorn / Led me & my companions’” (188-92). But Shelley seems aware that, like Rousseau, he is not among those who can forbear the dance; like the dead master, he is “one of those who have created, even / If it be but a world of agony” (294-95). Rousseau's experience, in his “April prime” (308), of seduction by nature away from a primal, imaginative vision, echoes Shelley's own experience, and interestingly what Shelley perceives as the experience of Wordsworth's “Immortality Ode.” (Indeed, it is not uncommon to read Rousseau's speech as a parody of Wordsworth's poem.) The malevolent seductress of Rousseau is described as a mysterious “shape all light” (352), a Wordsworthian conception of nature that according to Donald H. Reiman, “is composed of all that is ‘wonderful, or wise, or beautiful’ in the young Rousseau's experience, but as the product of a limited human imagination, she is still of earth, earthy” (quoted by Bewley 872). Bloom notes that Rousseau, drinking from the shape's “crystal glass / Mantling with bright Nepenthe” (358-59), forgets “everything in the mind's desire that had transcended nature, and so he falls victim to Life's destruction” (xlii). The lesson comes too late, however, to Shelley, for whom “life had become the destructive element in which perfect integrity and purity of heart and imagination were all but impossible” (Bewley 871).

In spite of its fragmentary nature, “The Triumph of Life” is a most impressive achievement. The influence of Dante was obviously beneficial in tightening Shelley's style and clarifying his images. But the points where Dante's influence ceases its penetration are most interesting in highlighting Shelley's distinctively modern concerns. The first thing one notices about Shelley's use of Dante is his secularization of his model's religious and allegorical approach. Like Dante, Shelley wants to write on the level of ideas, but these ideas are personal and secular, expressive not of a shared body of religious belief but of personal conviction and feeling. Thus, Shelley's vision is explained in psychological terms that are quite alien to Dante's belief and practice, though as one might point out, even modern religious poets like Eliot offer some “realistic” explanation for their visions. Perhaps by analogy with Virgil's inadequacy of faith in the Commedia, Rousseau is presented as a corrupted figure. But though his message is ambiguous, it suggests certainly a dark and infernal view of human life alien to Dante's larger view, but rather typically modern. Whether Shelley might have won through to a more positive view if he had lived to finish the poem is, of course, unanswerable, but doubtful, and perhaps beside the point. Dante provided him chiefly with an overarching metaphor, a poetic structure for investigating the hellish interiors of the modern soul, and it is perhaps in the nature of it that the investigation should be fragmentary.

Dante Rossetti's use of his namesake is similarly psychological and infernal. In the “Willowwood” sequence of The House of Life, the Dantean motif functions to expose the failure of love as a means of overcoming Narcissism. The dream imagery in these sonnets, while it provides the adequate psychological explanation necessary for a modern use of the Dantean motif, functions at the same time to undermine its validity as an objective vision. Thus, the “Willowwood” sonnets become a dark, Narcissistic fantasy, a nightmarish journey into a troubled self.

The “Willowwood” sonnets (#'s 49-52) appear near the end of the “Youth and Change” section, the first part of The House of Life, and signal a significant darkening of the seemingly more hopeful attitude about love that finds expression in such sonnets as “Silent Noon” (#19). In the earlier poem, as the lovers lie together in a pasture “'neath billowing skies that scatter and amass,” their moment is epiphanized, the landscape of “kingcup-fields” and “cow-parsley” is made “visible silence, still as the hour-glass.” Love transforms even the meanest constituents of nature into things of significant beauty and indeed plays the trick of bestowing timelessness on the lovers, offering them, “for deathless dower, / This close-companioned inarticulate hour / When twofold silence was the song of love.” Rossetti is not so innocent, however, as to mistake his epiphany for something more than a provisional assuagement of the condition of timefulness. On closer inspection, the insight of the poem appears deeply paradoxical. The “inarticulate hour” is also described as “winged,” for time, as perceived by human consciousness is never really still; an “hour-glass” is never still unless its sands have run out. Indeed, our only possible timelessness on earth is death. As Stephen Spector has argued, this notion is involved in and underlined by Rossetti's use of the sonnet form itself, with its inherent structural imbalance suggesting the ineluctable movement of time (54-58). Thus the “deathless dower” is really an epiphanic “moment's monument” of art with precedents in the sonnets of Shakespeare and Michelangelo. This is the only possible transformation into timelessness that the poem offers, and it represents something less selfless than a romantic ideal of love.

The “Willowwood” sonnets make use of the Dantean motif to explore the Narcissistic consequences of such love. As in all modern Dantean poems, a psychological explanation of the vision is intimated, in this case through impressionistic, dreamlike imagery and the dreamlike compression of the title (“Willowwood,” of course, is the wood of weeping, the forest of tears). Another suggestion of dreaming is the deliberate confusion of the speaker, Love, and the beloved, with the implication that the consciousness of the speaker embraces all the rest. The first sonnet begins with the speaker sitting “with Love upon a woodside well, / Leaning across the water, I and he.” Though the speaker and Love appear to be at least grammatically distinct at this point, we should keep in mind that the speaker “leaning across the water” is in the classic pose of Narcissus, implying rather his identity with Love. The image is not so simple, however, for Love makes “audible / That certain secret thing he had to tell” (though we might indeed say such things to ourselves), and this in turn comes “to be / The passionate voice I knew.” At this point, the image of Love changes to that of a female beloved: “his eyes beneath grew hers; / ... And as I stooped, her own lips rising there / Bubbled with brimming kisses at my mouth.” This seems on the surface at least a fairly straightforward rehearsal of the dream motif of a speaker meeting his beloved (the fact that she is a “lost” beloved suggests, perhaps, the influence of Milton's “Methought I saw my late espoused saint”). But the notion of Narcissus continues to govern in some sense throughout the poem, implying that the love of the speaker is somehow self-love. Like the young officer in Rilke's “Letzter Abend,” the speaker here sees a mirror image in his beloved, not her own. The myth of Narcissus is very clear about the dangers of such love, and they are suggested by the sonnet.

The next two sonnets of the “Willowwood” sequence are taken up with Love's song, though interestingly it is “meshed with half-remembrance hard to free,” arguing again for the omnipotence of the speaker's Narcissistic consciousness. Love sings not so much a song as a Dantean anecdote while the speaker and his beloved relive their days together, “the shades of those our days that had no tongue.” In Willowwood is “a dumb throng [the language here is interestingly close to Shelley's] / ... one form by every tree / All mournful forms, for each was I or she.” They engage in a “soul-wrung implacable close kiss,” but all the while make “broken moan” in their hopelessness. The kiss, which holds until Love has finished his song, is a sort of enabling talisman of the vision. In the third sonnet, Love addresses “all ye that walk in Willowwood / ... with hollow faces burning white.” These manifestations of vain love (“who so in vain have wooed / Your last hope lost, who so in vain invite / Your lips to that their unforgotten food”) are promised nothing but “one lifelong night” before they “again shall see the light.” Indeed, the speaker prays for a Lethean forgetfulness: “Better all life forget her than this thing, / That Willowwood should hold her wandering!” Willowwood, of course, suggests the speaker's mind in its dream state. The implication of these lines, therefore, is that he would drive her from his unconscious, where she lives on as an occasion for unbearable guilt.

The notion of guilt is reinforced in the final sonnet of the series as Love ends his song: “when the song died did the kiss unclose; / And her face fell back drowned, and was as gray / As its gray eyes.” If the speaker of the poem may be identified to any degree with Rossetti himself, then the lost beloved of the poem is very likely Rossetti's wife, Elizabeth Siddal, who had died of tuberculosis six years before the probable date of composition. The image of her falling “back drowned” may be seen as something more than a colorful arabesque. It suggests rather a surcharge of guilt in the form of negligence on the part of the speaker who cannot help letting her fall back.5 In the context of the poem, this guilt manifests itself in the Narcissism that calls into doubt any unclouded sense of youthful, idealistic love. The Narcissistic confusion of identities, set up in the first sonnet, rises to a chilling climax in this final poem of the sequence:

Only I know that I leaned low and drank

A long draft from the water where she sank,

Her breath and all her tears and all her soul: