A life-long resident of New Jersey, Jeffery Triggs received a Ph. D. from Rutgers in 1986, where he taught English from 1978 to 1987. From 1989 to 1999 he was the director of the Oxford English Dictionary's North American Reading Program. From 1999 through 2001, he worked at AT&T Labs. Since 2002 he has worked for the Rutgers University Libraries on digital library projects. He resides presently in Madison, New Jersey, with his wife Sara. They have two children, Charlotte Elena and Jeffery David.

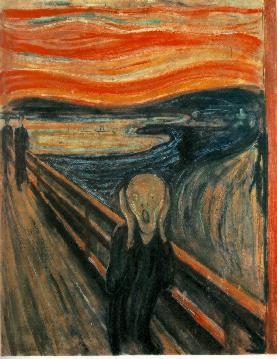

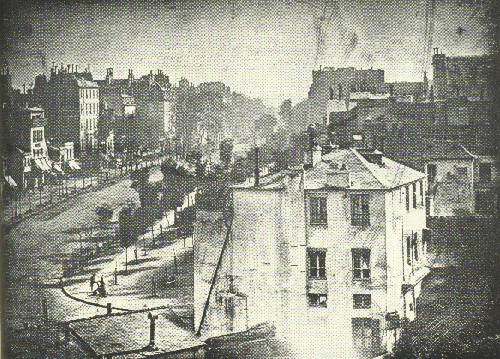

Poems in this collection have appeared first in The Literary Review (“Attic Stele on a Child's Tomb”, “For Charlotte Elena, Age 10, January 2, 1993”), The Journal of New Jersey Poets (“Horse Dying at his Cart,” “Death Mask of a Girl Drowned in Paris — 1895,” “Hamlet knew it,” “Edvard Munch — Shriek 1910,” “Antiques”), Gryphon (“Paris Boulevard”), Interim (“Lear's Wife”), Art Times (“Scene from Swan Lake”), International Poetry Review (“Sargent—Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose,” “Rose of Sharon”).

I. The Long Way Home

Funeral for a Worm

For Tati and Grandpa

Why might a chicken have crossed the road?

Duh. Because the sidewalk ahead was dug up. Q.E.D.

And this only one of many things we ponder

as the sun follows us slowly through the neighborhood.

If I remember correctly, Rilke was right:

children see things low to the ground, the things

we giants, lost in our abstractions, miss:

seed-pods we crush routinely underfoot,

stray feathers, a dimpled stone, mud-sleek twigs

that emerge from the puddles after downpoured rain.

I can still picture a day like this with my grandfather.

With his cardigan, perhaps with a cigar in hand,

we slow march up and down the road together,

though he avoids the puddles I delight to splash in,

attentive as only someone with new, spare time can be.

Today the May sun dries the puddles after a rain,

stranding earthworms that washed up in the road.

They frighten me, though the live ones merely struggle

to win back to the soft, safe, burrowy ground.

With a twig we lift one crushed worm from the road

and give it as best we can a cortège and decent burial.

I wonder sometimes if you quietly conjured the needed music,

Andante con moto, still vivid memories

of the great orchestra in which you'd recently played,

and as yet meant nothing to me.

For Sara

Even in the rain the early bird comes out.

The one we've listened to these years

Who woke us that first morning

Now sings the song that's knitted us together.

Haiku

For Sara

Touch of fingered yarn,

Click of the wooden needles.

Sunset already.

俳句

Light, wet snow in March

Paints evergreens with blossoms.

We yearn for the spring.

Washing Up

When I wash dishes, glasses, silverware, old pans,

I feel in them the touch of the long dead.

I hold what they held, my fingers trace the cracks

that run through porcelain like lazy streams

traveling from their sources in some forgotten time.

I touch the smooth curves of the bowls, as with the potter's hands.

I watch the kitchen light glister in facets of cut crystal

or on the rims of glass still blushing from the evening's wine.

My mother's silverware, my grandmother's iron pans,

the bowls in which our bread has risen, over and over,

I feel in them the touch of long lost selves.

For Tati

Wide-eyed with wonder, we listen to your first spring

Through open windows whispering with breeze,

The same birdsong I've heard now how many years,

Edenic noises to draw forth the earliest sun.

Wide-eyed with wonder we see, as for the first time,

The buds burst into bloom, the leaves unfurl,

Thousands of them, millions perhaps, that seem to float

Windily over the lulling, rocking carriage you are in.

Low to the ground, we trace the wavy texture of the grass,

Grown green now and lush in molting May.

Each day the sun grows warmer, longer, strong

Enough perhaps to lift you lightly from your knees,

Wide-eyed toward the wondrous blue sky,

Forever beckoning and forever young.

I, Tati

On a cold, damp day, otherwise

quite ordinary, dreary as all February,

something utterly amazing happens. Pen in hand,

you mark a paper with your name: T@tTI.

Or so it looks to me — pure calligraphy.

From this oath, “I, Tati”, all the future must proceed,

schoolworks, mortgage signings, pure poetry,

everything you will mark one day as your own.

Privet Blossoms

I keep forgetting to write this poem —

its subject slight as the tiny hedge flowers

that welcome summer, filling the walkways

with a glorious scent that belies their humble presence.

Redolent of the idle summers of my youth,

for weeks now they have blessed each morning walk,

reminding me, before the business of the day takes hold,

of the sheer beauty of being so easy to forget.

Heavenly blues

They are quite difficult really. No volunteers

Spring eagerly to life when summer beckons.

They must be coaxed from seed, positioned

Just so, and favored with the weather's luck.

Even then, sometimes they stubbornly refuse

To bloom — but when they do we have The Blue Flower

Itself, Mary's hue, the keys to very heaven.

Suffused with the morning sun, they glow as with sources

Of their own so brightly that as the day wears on

They consume themselves. Daily generations

Furl and unfurl thus, always different and the same,

And comforting as the weeks pass by. Near the end,

When daylight shortens and the nights grow cool,

They bloom abundantly, as though desperate now

For more living days before the frost that will lay them waste.

Berlioz on the Beach

For Sara

It's just an earworm, really,

a Faustian will o' the wisp

from the moments before WQXR gave up the ghost

somewhere on the Parkway and turned to dust.

But enough. Now the crashing waves,

the seagulls' cries are transfigured

by whimsical, whirly music. Can it be

that no one else here listens?

They go about their beachy business

as before, filling sand buckets,

paddling in the waves, scarfing down

sandwiches and cokes, turning pages,

or simply soaking sun rays in the seaborne breeze.

But for me all is changed, changed utterly

perhaps. I can almost make out,

silhouette along the shore, a figure walking

in a frock coat, a peacock spread of hair,

toward the blue point where the horizons merge.

Rauschen

For Sara

Today we don't hear it the way Eichendorff did

Shwooshing night and day through primordial forests

Godhood made somehow audible in Nature. We hear it,

When we do, against the background humming of the highway

Or the noise of the landscapers' machines, insisting weed-whackers

Leaf-blowers, airplanes, sport utilities,

Perhaps a siren or two transporting the fallen of this world.

But when our world intermits, as it sometimes seems to do,

When the leaves are full of summer still and the first

Autumnal wind is up, our gaze is drawn

To the rustling crowd above us, and the sound,

With its deep, slow harmonies, is overwhelming.

Ah, this is what they knew, the old poets!

And for a time at least our ageless spirits mingle.

Lazarus of Bethany

Young Rembrandt shows you best perhaps,

your ashen features barely distinguishable

from the molding graveclothes. You struggle

visibly to lift yourself from the opened tomb.

The onlookers, bathed in light, are by turns

suspicious, tentative, astonished at the event,

even the one whose raised hand seems to draw you up.

You have known death already: four days, an eternity

outside time, your memories dispersed apart, your body

given to inexorable dissolution. That much is the same.

As you blink now uncertainly in the light, how can it feel

to be drawn back into a disintegrated body so changed

you do not know it? to look upon smiling faces somehow

infinitely strange? And in the end what was it for?

The others, the women, of course are happy, relieved,

but they cannot know the horrors you passed through

and now must face again. For you rise now, not into

a kingdom of heaven, but once again into the darkling world.

The Tenth Leper

Until he was chosen by the disease, the tenth leper

Was just like anybody else. You couldn't have picked him

Out from a crowded street on any given day.

And even when the bacteria had taken root and the sores

Declared themselves, when the numbness set in so

That he could not feel the rocks of the road

Break off his toes; when he was shunned now

By the good people, the normal, lucky ones,

He seemed still like any ordinary leper, so far gone

That he was past hoping for a miracle.

When one came to pass, when the man on the road

Waved his hand at a whole group of them at once,

Did he summon from somewhere deep in him the feelings,

The hopes, the common decencies of man alive?

Liebestod

In the official police photos, Stefan Zweig and his girl,

Young Lotte, can be seen lying side by side,

Primly propped, he in his sweat-stained shirt and tie,

She in her house dress. Their lips are pursed and chaste.

Their fingers gently touch each other as though

They were shy, young lovers on a first date.

Only the empty bottles on the night stand speak

Of something gone amiss. Things are not as they seem.

I have seen a different view. The same iron bed, same bottles

And same clothes, only here disheveled. He holds her

In his arms as only a practiced lover knows to do,

His mouth is agape, as if he strained for one last kiss.

Not knowing better, one might almost think

They moved in death, death imitating art.

Crickets

For my friend, Marcantonio Crespi

It's time now for the hard poems, the ones

you never wanted to write at all, the ones

pried out like aching teeth.

It's September now, and time you were back

from wherever it was you spent your summer this year.

The semester is soon to begin, full of business,

new students, new beginnings.

We have a standing dinner date just about now.

A quick handshake of welcome, a glass of wine,

a joke or two, and we pick up where we left off.

It's happened just this way for how many years now?

Likely as not the evening stretches on

after dinner: brandy and cigarettes on the porch

in the cool of the late-summer evening, and talk,

always good, witty talk to catch us up,

We round our lives with such words. In September,

ever wistful, the dark comes earlier,

and the crickets fill our ears, reminding us

of the chill night, surely soon to come,

when they'll fall silent. We're poets together,

after all, and death surrounds poets, mitten im Leben

as Rilke put it. Death is a thought we always

entertain, at least abstractly, theoretically.

Whether your “mort”, my “death”, even Rilke's “Tod”,

the word itself is delicious. “Easeful death” —

one might well be half in love with that.

On some level I still think it can't be true! at least not yet!

But right away I knew. You were in Switzerland

like so many times, but different this time,

after the hospital stays, the gruesome treatments,

the dread, mysterious bug striking and clinging

to you, stealing all joy of life, making you,

suddenly, unforgivingly a mid-life invalid.

The heart that over the years watched and received

finally gave out. So many memories

roared now tsunami-like over my thoughts,

which seemed to tear away from me out of control.

I remembered our last phone call, our last meeting

sporting now their terrible, unexpected adjectives.

I thought of a dozen things I longed to talk with you about —

movies, books, events, current now only for me.

No literary savor in this ache.

Dark house, by which once more I stand...

I actually drove by your house once, almost by accident,

pulled on by some half-conscious wish that made

me take wrong turns until the road itself insisted.

The shutters, the curtains still the same, the lights turned out.

Oh Marc, oh Marcantonio, Marcantoine.

(How shall I call you now?)

I write this for you with one of your own pens

still full of ink, still bearing, as it were,

its unborn lines of poetry, a final metaphor

whose difficult birth I guess at from the chewed tip.

So much of life passes away in mere habit,

irksome tasks or duties that do the work

of holding off dread certainty a while.

We never know, really, when we do something

for the last time. Oh Marcantoine,

I can see you rising to greet me at the door,

the table ready with cheese and biscuits and wine,

a candle flickering in the evening light.

This time it is I who have much to tell you

as we pick up where we left off before.

Lohengrin

For Marcantonio Crespi

When you first breezed into our lives, a young knight

seemingly out of nowhere, we didn't know your allergy to Wagner

and I'm afraid for every evening of wine and Puccini arias

I inflicted hours of Lieder on you, while you submitted bravely

in the spirit of young friendship. No surprise then that, as the chance arose,

we took you to Lohengrin, that magnificent fairy tale

even non-Wagnerians claim to like. You held out silently,

not wishing to seem ungrateful. while we thrilled to the usual scenes:

Else's Traum, the knight's arrival towed by a stage-prop swan,

the boisterous, brassy, German sounds that filled the hall.

Perhaps it was only the champagne in the final intermission

that made you admit to us how much you loathed it all.

And how I cringed then when the third act began fortissimo

and wished the wedding and the love music away, the magic muted

when the knight sang out his name and vanished in the misty lake.

The curtain closed on Wagner, but our friendship started new that night,

knowing ourselves different, and lasted through long years of business:

marriages, children, funerals, jobs that kept us far apart,

and through the anguished years of inexplicable decline,

the secret illness that gripped you and would not let go.

I listen now to the anxious chorus cry "der Schwan, der Schwan,"

and to the achingly beautiful notes of renunciation, of loss,

and think of you now, my unlikely swan knight, as you depart

one last time over the misty lake, mysteriously as you arrived,

and we remain, non-operatic creatures that we are,

to go on day by day among the living.

For Marcantonio Crespi

In which heaven shall I find you then?

I fear we failed to make arrangements for that

when last we spoke, and now I am at a loss.

Will it be Capri-blue, or like this mottled sky

chill with New Jersey spring? How will I even know you

there? Will you be young again, vacation tanned

as when we met, or gray with too few years?

Will we meet point to point, as if once more in time,

or everywhere and every while at once?

Laundry

For my mother, Helen Triggs

As I still see it, the house is flooded with light,

morning light most likely, perhaps in February

intensified by the snowy yard outside. I follow you

from room to room, each with its gauzy shafts of light

that flame the dust and gleam the waxed wood 1950s floors.

Now we head down to the windowless dark of the laundry

where I help clean the delicious lint from the dryer.

It has an otherworldly softness, an inutility

that begs for more of this lulling time, for play.

I sense the rich brown cascade of your hair, so long

to me then, though the evidence of pictures shows it

merely shoulder-length. In the bedrooms once again

you fling the white sheets aloft, aglow with morning light

and snap them so that they settle gently, perfectly

on the waiting matresses. I want to reach out for them

clean and laundry-warm. I want this moment to stay,

and though I am only four, I know somehow that it will not.

Merry Widow Waltz

For my mother

The old Oldsmobile seemed almost to float, slowly

inexorably as it neared the schoolyard. Sometimes

we'd beguile this anxious time with the car radio

blaring, say, ”Downtown“ or ”These Boots are Made for Walking“.

It was hard to imagine Petula Clarke in the hip and distant city

I would one day visit, but the sounds mitigated, somehow,

the day of fourth grade misery that grew more real as we passed

each stop sign on the way, and then the crossing guards

with their silver badges who waved us on the last leg.

I still remember the ache of being there, the watched clocks

teasing me with their stubborn stillness before, sprung,

they'd softly thud each minute of the passing day.

Sometimes instead of the radio you'd hum your own melodies,

Lehár's ”Merry Widow Waltz“, lovely and lulling and lush.

This is how I'd hear it, even now - not glamorous of Vienna

sung by some elegant diva under the dimmed chandeliers

of the Met, but softly hummed as we wended our way home.

Music in the Rain

For my mother

In the morning, in a cool, mid May,

rain glows all windows green and gray,

sheets of it stipple the eastern panes

as we attend to lovely strains,

Beethoven, perhaps, or Richard Strauss,

that fill the corners of our house.

No need for words. The music binds

the thoughts of unconnected minds,

treasure we carry separate ways

as these moments travel into days.

Scenes like this now come to me

from a dim recess of memory

as fresh and vivid as the spring

that gives the day such coloring.

The End of the World For David Triggs

In those New Jersey summer days when a/c was scarce

but gas quite plentiful, we would, likely as not, escape the heat

by driving “to the country” — if only through New Vernon,

near Madison, but rural enough. My father still drove in those days

my mother next to him, and three of us tucked in the back seat.

He liked to scare and amuse us, driving suddenly on the dirt path

next to the Tuttle oak, a huge old tree allowed to remain

in the middle of Prospect Street. George Washington,

according to the legend, once tied his horse to it.

Along one country road we always thrilled at “the end of the world”.

Shuttered with overhanging trees, the road wound up a hill

at whose crest, simply and suddenly, it vanished into the sky.

We always waited for it eagerly with a kind of mock terror,

only to be relieved when at the top we saw a pleasant meadow

slope gently downward full of wild flowers and late summer light.

The distant goal then, often as not, was Jockey Hollow Park,

surrounded by sets of funny-looking, split-rail fences.

Here was another old horse tale. The young girl, Tempe Wick,

fearing it's confiscation by Washington's soldiers, had hidden

her horse in the bedroom of her house. If we had time, we'd stop there

to wander a bit. Leaning on a split-rail, we would scan for deer

shyly entering the apple orchard. Deer were not suburb "pests" back then,

as so often now, and rare sightings. We waited through the twilight

eager for a glimpse — all one usually got, as they'd bound away

at first sight of us, hurdling the spiky fences with surprising grace.

As the lingering light paled finally into summer dusk,

it was time to pile back in the Oldsmobile and head home.

Perhaps an ice cream waited for us on the way. My father

always delivered us safely home and tired enough for bed.

I happened to be driving there today, and wondered as I went

if my father, when he faced suddenly his own end of the world,

passed through at wonted speed and found there a meadow as alluring.

Magnolias 2000

Eager in the rich-proud service of the spring,

they bloom early and without stint, holding back

nothing, like some more cautious plants; indeed,

they give so much of themselves that when April,

as it sometimes does, plays a malicious trick

(like this snow, no sooner here than gone),

they cannot quite pull back and weather through.

The opened buds fill up in cones of snow.

Their delicate, pink skins, shocked by the cold,

tremble with the unaccustomed, icy weight.

And then they droop and wither, suddenly brown,

eyesores quite out of place among the other

flowers that hasten onward now the hourly,

inexorable work the season had begun.

Nature

The dog walking on his hind legs may seem,

for a time, remarkable. It is not, after all,

an everyday occurance. It is full of amusement

for the leisured classes. Often, they condescend

to hail the dog with toasts to such abilities

as even he grows shame-faced at the mention of.

But soon they all tire of the game. The great ones

return to their affairs, while the poor beast,

though he may venture a few more steps unattended,

returns to a four-footedness somehow less natural

than before, as though, from having striven

beyond himself, he was now fallen more lowly.

Avoiding now even the casual looks of strangers,

he cringes in a doggy way, and lets his tail

drag downward and curl between his quivery legs.

But eventually his true nature reasserts itself:

four good legs carry him swiftly and more surely

than two, and blithely he courses where he wants to go.

The Wolf at the Door

a Dream

He is not at all like my dog Blizzard,

the friendly Samoyed who watches out for my return,

wagging his tail, ears back, glistening white

in the welcoming, warm brightness of the kitchen.

The wolf at the door is scruffy, dirty, dark.

Only his teeth gleam white with a vicious grin

as he eyes me and moves near, silent and menacing.

He's met me now. There is no place now to run.

Without thinking, I leap on him, wrestle him,

pin him back with all my weight and strength,

the strong jaws held firmly for the moment shut.

But the malignant grin remains, mocking me.

I cannot let go even for an instant now,

though my arms ache and strength begins to wane.

One slip, and the razory canines will surely slash

my arms, my wrists, the face brought down so close.

I wonder now if there is even time to wake.

Christmas Morning

1999

I am sure that somewhere, even now,

machines are whirring, jet planes landing or taking off,

hard-drives spinning with their odd, muffled chortles.

But here the morning passes from silence through silence,

so that, going out into the rinsed December sunlight,

the only sound is wind itself, sweeping

the frigid air, spreading plumes of chimney smoke.

Hard as you try to populate this silence,

say, with a shivering tangle of bare branches,

or the raucous descent of some few, spare crows,

it insists upon itself. The sounds are strange —

the flapping of wings, the odd “caw”, “caw” — eerily

discrete, distinct, and quickly overwhelmed:

like pauses in a kind of masterful, negative music

where you may hear, if you can listen,

modern echoes of the ancient miracle.

Marblehead — August 1984

You'll remember how we wandered that day

(having somehow escaped the dead museums of Salem)

the narrow, winding streets, walled or picketed,

how we spied the weathered, shuttered “sailors' cottages”

with their tiny closed gardens, often with keyhole gates

and bright with hydrangeas or rose of sharon.

It was easy to lift Charlotte then, and one could walk

for hours not heading anywhere in particular.

And then to happen on the bay, bobbing with sails

in the glistening sunlight. The blues of water and sky,

the whites of cloud and sail, the blazoned boats

and craggy, background shore — all seemed somehow painted

for us with youthful impressionism. Glorious

to be far away from home that day, we three

carelessly alive, thinking neither of the past

nor the future that waited for us in its dim coils.

Twenty Years to Life

For Sara, May 17, 2000

Rain-rinsed, sunlit, a-twitter with every birdcall

possible in May, the morning waits for us;

in sweeping, sustenuto passages of breeze,

the wind-chimes, two of them now, ring out for us.

Twenty years have brought us to this day,

to this garden greener than memory,

to this huge oak tree, spreading, swaying

in the breeze, in which, if I look deeply,

I can still see the lovely, white-veiled face

with tremulous eyes coming to meet me,

I can still feel my own heart beat with anticipation,

as if for a journey; and then, veil lifted,

the softening smile, the calm determination for departure.

Twenty years have brought us to this day

which passes slowly, solemnly almost,

the light stepping carefully about the yard,

drawing the seedling flowers of last weekend.

Its ceremony refuses interruptions:

the importuning cries of children, who burst

awake now, ready to go like wind-up toys,

the roaring of a vacuum cleaner, car doors

clanging shut, the passing of some siren.

The birds themselves are at work now, fetching

twigs and straw for their nesting in our soffits.

Shopping, laundry, mealtimes have their cycles too,

and follow one another faster than the shadows

that begin to lengthen and mottle the green lawn.

But I can still make out the trusting green eyes,

the gentle hand held steady to accept its ring.

Twenty years have brought us to this day

which hums along now, like so many others.

The sun, traveled round, shines now from somewhere

behind us; we look out, spectators of the shade,

upon the honeysuckled breezes of the afternoon,

you with your knitting, I through puffs of pipe smoke.

Dinner, sunset, upon us, gone. No need of words

after all this time, when the well-honed gesture, glance,

or private joke still carry years of meaning.

And perhaps, late in the warm fragrant dark,

wind-chimes will still sound out on the deserted porch,

a look or a familiar shape, unseen but sensed

and still loved and the old thrill will come upon us both.

Intermission

Diffusely lit, the curved walls covered with red velvet

spiral slowly down the stairs from the upper galleries.

Turiddu, bumbling oaf, has had his Mafia-like demise.

Soon Pagliaccio, make-up half on, will sing in anguish

at the betrayal of his Nedda (namesake of my aunt's cat);

the great, dramatic killings, and the final cry:

La commedia è finita. But it is not over yet.

Crowds mingle as with one studied nonchalance.

The usual cast of characters: two women, middle-aged,

in necklaces, bracelets, their best dresses, chat about husbands,

bosses, the dreariness of it all. Across the way

a pair of sleek young men in dark shirts (they have known it all already)

maneuver toward the door to the outside balcony, cigarettes

ready in hand. A stately old woman orders champagne with an accent

from somewhere or another. A young man in tweeds, no tie, a three-days'

growth of beard (perhaps a music student), heads back in early.

An older, Brooks Brothers white male, managing two cocktails,

looks about as though he were enduring this for someone special.

Not much has changed in thirty years, except perhaps

the cell phones that keep popping out unexpectedly

and the earrings on a number of the younger men.

I scan the room looking for someone who is not there,

not queuing at the bar or water-fountain, not lingering

under the two gaudy, great Chagalls, not sneaking

a quick cigarette in the anonymous dark of the outside balcony.

He would be sixteen or seventeen, a somewhat awkward boy

masking his shyness in the seeming elegance

of his blue, pin-striped suit (reserved for such occasions);

dark-haired and with a stern, fixed look that might say:

“I am the poet of this place if you only knew. Of course,

I would rather this were Wagner, as I yearn for serious things.

My life has little else to occupy it at this moment

than dreams of poetry and music and great, vindicating,

laureled fame that the future, surely, will bring to me.”

But it is no use. If he is here, he has become someone else,

perhaps quite harmlessly middle-aged, keeping his secrets now,

melding seamlessly with the rest, who pass this brief time

waiting for the next act to begin.

Central Park, Sunday

For SaraThis day will bear remembering, for its fair weather soul

that somehow led our strolling lakewards here. For now,

we pause unharried: nothing matters but the sun-gilded sails

mastered by unseen hands of children. The city

stands back awhile, the summer crowds blend round us

in one great smile. Across the lake, checking his bike

(an upturned hat some feet behind), the itinerant tenor

stands at the verge and breaks into wind-buffeted song.

At the Carroll monument a clown magnets small children

to his busy trade. We sit and wait and wait

as under some hypnosis of the wind-blown waves.

The great tall buildings that look over us seem now

somehow benign, emptied of all business, their fearsome

energy coiled, poised. They wait and wait,

as loath to monday as we are to pick up our lives again.

For what? Surely, here, now, as each wave laps the shore

as the singer washes down a song with Evian

as the clown does up a balloon like a lion

as we linger with another ice-cream cone

surely for this one day there is no time.

Vacation

The first day of a vacation is always cloudless, blue,

wherever it may be, in the mountains or by the ocean,

in some great modern or medieval city, as long

as it is, as it must be, elsewhere: plan or not, rain or shine.

The bad things that might happen are still unknown;

the evils of the old life remain safely behind.

On the first day of a vacation the strange, morning birds

charm as no other, the foreign pillows are ethereally soft,

the hotel's coffee seems, somehow, richer than one's own,

the daylight brighter and the night more fine.

The bad things that will happen remain unknown.

The evils of the old life are still safely behind.

Pelicans

At the beaches of Costa Rica the pelicans

fly by like fighter planes in strict formations,

eight or ten, over the glistening water.

Now and then one dives toward the surface,

an old Stuka bomber ready to strafe,

but the target is some fish unseen by us.

If he is lucky, he struggles back to his altitude

with the squirming capture in his long beak.

Otherwise he'll fly low and solo over the breakers

hungry for a kill before he might rejoin his fellows.

Worker Bees

Disoriented by the sudden change of weather,

on a September morning they cling to what's left of the hydrangeas

and buddleia, attempting still what they know best,

all they have known, which can no longer save them.

The air fills now with the steady dirge of the crickets.

The light comes later now with its remembrance of summer warmth,

and glances sooner away, leaving long, evening shadows

cool and death-dealing to all without another season in their DNA.

Einsamkeit

The cold morning air and winter light perhaps,

the odd, deliciously transgressive feeling of the sick-day

and in an instant I become again a troubled teen,

playing hooky from the hated school. Left alone,

I would spend long mornings listening to Schumann

or improvising on the piano in my pathetic, untrained way.

One year — I can't remember why — we failed to drain the pool

so that the water froze with Winter and we had months of ice,

a kind of private rink. At home alone, in the cold morning light,

I would put on skates and spend hours gliding back and forth

over the glassy surface, cutting figure eights (my math that year).

Loneliness and pleasure, shining, seamed with gilt like a tiger-eye,

attended these occasions, as they do today. Then I waited,

coiling for a life I could not imagine. And now?

Awaiting the unimaginable shuffle, I fold away from the world again

into a self decades more crowded now, but still one and whole.

Basketball

On a winter day, without snow or ice, the sound

Of a basketball, repeatedly dribbled and thrown

Beats out the slow time of Sunday morning.

A solitary boy is practicing his hoops. Without

Some seven-footer to block his shots, he is brilliant,

Outwitting all imaginary opponents,

Looping long, curving three-pointers into the net,

Over and over, bouncing the ball with abandon

On the empty street. In the distance church bells

Ring out as if to celebrate each point.

He doesn't see me watching. He will no doubt

Grow out of the game some day; the backstop,

Rusty and unused, will go to the compactor.

But years from now, perhaps watching another

Boy at play, he will recall the triumphs of this day.

Snow

The night is lit with snow

falling through the lamplights

capping the dark hedges and the walls.

In the distance a train passes. The snow

glisters on the powerlines. The sky is sepiaed

with reflected light. One can see in this dark.

Why is it beautiful to me? Why not a horror,

cold coating death? Yet the flakes caress

all things, and transfigure with their caress.

On a night like this, one might believe

in the transmigration of souls. One might

believe, even as a late car carves two tracks

of darkness in the road, in a caressing God.

The Long Way Home

Christmas week invites a kind of laziness,

deliberate movement, contemplative of things past,

and so, given the choice, on a cool, gray morning

I take the long way home. The streets, familiar

from bicycling or walking in my youth,

seem hardly different now, winding as they would,

but the neighborhoods are changed, strange, so foreign

I hardly know them. The older shade trees, pen-knifed

with youthful hope by a boy walking from school,

have vanished with a future whose time has now passed.

The young maples that neatly lined my old street, brightening

the changing seasons with red leaves, are still there,

but now misshapen, spreading haphazard branches

awkwardly through the power lines. The houses

are changed too, warted with ungainly additions

or simply uprooted to make way for outsized McMansions

that swallow whole the yards where we tossed our footballs.

Now and then I recognize a house that's not been changed.

I wonder if I might stop there, ring once more,

and see the door open to a familiar face,

perhaps my old friend eager to come out and play.

But that cannot be. If he were there, he'd be

no longer blond or young, and besides all that

I have a living home I must get back to now.

Layers

They're not all bad, the new things,

much as one dislikes admitting it. Yet on the long road home

I fancy much in truth no longer there:

that rust-colored barn where we stopped once

to peek at the goats with their “mystic”, slanted eyes,

the empty field where, as a child, I had a tractor ride.

[Today outsized McMansions own the view.]

Beyond there, somewhere, is the duck pond with its falls.

But even the grand houses, the ones we sought glimpses of,

have changed: the white-wood, farmhouse sports a brickface

and fake columns now, tripled in size. The town itself,

which I thought would never change, is different now:

most of the old shops gone, though a few names still

cling in fading paint to the upper reaches of brick walls.

New, fancy sidewalks, new storefronts, new people now.

When I imagined living here, I did not realize

here was now.

According to the real estate agents

every “property” is a “home” to be bought as such.

Thus you can buy “townhomes”, “executive homes”,

but never now a “house” in which to make a home,

as we did. In the houses I have known there were many homes,

for each home is made by people, two or three gathering together

in a space and for a time. A house's homes are born

and live and eventually, like all living things, they die.

They are made with passions, boredom, clutter, dinner smells,

the dust of days laid on in generous layers.

Our first home (ah, yes, renters make them too)

was the second floor of a Victorian house

on a street with gray, slate sidewalks rising

obligingly over the roots of the larger trees.

I can still see its elaborate, carved moldings

its wide pine floors, the wavy, hundred year old glass

of the windows; I hear the creak of the back staircase;

I smell its ancient wood, like my grandfather's house.

We moved there the first of June. I remember waking

next morning to the sounds of the birds and sweet breezes

wafting through the window screen.

Today

in another house more than a generation beyond

we heard birds like that again, and felt again

the soft, cool breeze: and that June morning,

still there full of youth and hope, somehow eastered in me.

Though not a molecule of our old selves remain,

I am still I, you are you; we've shared this journey in place

registering change and yet the same.

A self persists, perhaps a soul expanding time,

a tree of girth that still knows all its sapling rings within.

June 3, 2017, New Jersey

At 4:30 in the morning you can hear, well, not a pin drop(I just tested that), but all the early birds at song,

the soft padded steps of the house cat, the snoring dogs,

the sound of a distant jet that pours through the birds.

And suddenly, at 4:45, it all goes silent for a while

to give the sky, still quite dark, time to catch up.

A dull gray now to the east, just bright enough

to make the boughs appear again on the white oak.

At 5 new birds begin to sing in antiphonal choirs

far and near to home; a train engine hustles by

before the day's usual service can begin.

And now the mourning dove enters with measured,

soft intervals. Oh what a world to wake to:

this contrapuntal and suburban dawn!

II. Archeology of Feeling

L'envoi

Hands connected at the tips, held out

as if in beggarliness. What will come?

An airplane soars above, destination Heathrow,

perhaps. On the ground it does not matter.

What will come? Eyes lift planeward and beyond.

Orion beckons; the Pleiades draw one

into their ever-complicating mystery.

Around one, the cold universe draws its breath.

Morning

O pflaumenleichte Zeit der dunkeln Fruhe!

Welch' neue Welt erwickelst Du in mir?

| Mörike |

The horizon forms itself first, a silhouette

fringed with light. Then all the shapes

hidden in darkness, as in gray mist, emerge,

lighten almost imperceptibly, compelled

with each passing moment. The birds know this.

They break into songs, first one, then others.

I keep to bed, though the pillows have taken shapes

wrought by the nightlong twisting of my dreams

that wither quickly now. Their terrors gone?

What new world indeed brightens behind the shades?

On a Winter Morning, before Sunrise

by Eduard Mörike

O feathery light time of the early dawn!

what new world would you awake in me?

What is it that suddenly, now in you

I glow with soft voluptuousness of my being?

My soul is like a crystal now,

untouched yet by a false ray of light;

my spirit seems to flow, it seems to rest,

open to powers, miraculous and near by,

that from the clear belt of blue air

call out a magic word before my senses.

With bright eyes I almost seem to sway;

I close them so the dream cannot escape.

Am I gazing into the bright fairies’ realm?

Who laid that vivid swarm of images and thoughts

at the very gateway of my heart,

that, shining, bathe themselves in this bosom

like goldfish in a garden pond?

And soon I hear the sound of shepherds’ flutes,

as round the crib upon that wondrous night,

soon wine-crowned, happy songs of youth;

who has brought that peace-blessed crowd

outside my sorry walls?

And what a feeling of enraptured strength,

in which my mind guides itself freshly afar!

Drenched by the first mark of today

I am heartened to each good work.

The soul flies as far as the reach of heaven,

the genius in me rejoices! Yet say,

why does my gaze grow damp with melancholy?

Is it a lost happiness that softens me?

Or something growing that I carry in my heart?

Spirit, go forth! Here there is no standing still:

a moment’s time bears everything away!

But look, on the horizon the drapes already rise!

It dreams of the day, the night has fled;

the purple lips, which lay closed before

breathe, half opened now, sweet breaths:

Suddenly the eye flashes, and like a god of day,

with a spring the royal flight begins!

Archeology of Feeling

A thought once spoken is a lie.

| Tyutchev, Silentium |

Language occults them so very thoroughly,

(these secret thoughts that drive us day by day

yet cannot confess themselves in grammar)

that you must merely guess at them, infer

like the astronomer who senses a new planet

from its slight pull of orbit on a star.

Music, perhaps, might get you closer to them,

Schopenhauer's perfect intuition

of will, a kind of innerliness exposed;

but music, timeful and prearticulate,

intermits in vast silences with each rest.

Poems would entomb them. Yet even here

only rarely, as through a fluke of nature,

will you find quick-frozen, perfect sacrificed

remains, ice-maidens of feeling on whose slender

arms hairs still stand in the excitement of creation.

More likely you will see here merely fossils

hardened round the feelings they'd delineate,

deathmasks whose chapfallen features you peruse

searching for hints of the vanished life within,

shards, fragments of a sensibility

scattered in the ground. You must dig for all,

brush, wash, assemble, re-imagine what was,

in the instance, a twinge of envy, or groan of despair,

delight, or gravitation of pure love,

lazy satisfaction, horror of death.

And feeling their deep silence give them breath.

Kinderszenen

It never rains when I think about those years;

always sun, though cold, a sort of February daylight.

Usually I'll be reading, listening to Brahms or Schumann

records. Always alone. But the picture window

with its unchanging scene: blue sky, gray woods

across the snowy road, is always bright.

As no one's there, often I'll settle at the piano,

“dreaming with the pedal down.” Suites and serenades,

whole symphonies pour out with no audience but me.

Of course my play is clumsy and wrong-fingered,

but the ear's a fine, self-serving editor, striking

blundered notes, adding here a trill or there

a thrilling run, muting the default fortissimo.

I took one lesson only. My aunt, the real pianist,

sat with me as I tried the Minuet in G.

Beginner stuff, but nice, needing a real left hand

and proper fingers, the happy gift of scales.

Softer there. Fourth finger for that. Legato.

Keep your fingers bent, your wrists parallel.

Practice one hand first and then the other.

For three whole days I worked at left-hand scales.

Perhaps with diligence, or Schumann's “seating pants”...

I thought of Rubinstein beginning at nineteen —

perhaps it was not too late to do things right,

another lesson in a week — but the week became forever.

The musician fled me, though his clubfooted symphonies

continued quite some while, (I can still hear one solo

played on a horn above soft, tremolo strings —

when I write today, it's right here obbligato

if you only heard...), but my best dream was already gone.

As one knows, without having to look out a window,

that the light has changed, a storm is coming on,

I'd know to start dreaming something else, something

for late starters, though it too require years

of practice, years of dedication, something

needing no teacher, though it aspire, silently,

to the condition of music after all.

Midlife Mirrors

Drei-und-Zwanzig Jahre alt, und Nichts für Ewigkeit getan.

| Schiller |

Perhaps it's just another bad hair day.

As I try to hold that thought, the mirror winces.

How did I ever get to be you? It can't be true.

That weary shabbiness about the eyes that once

looked piercingly at the great world, the gray hairs

insinuating near the temples — flags of surrender —

this is not me, surely; this is not me,

hardly more than a boy yet, just getting a handle

on things, still arming for the battles yet to come...

I'll try some irony, an arch look

about the brows, a disapproving scowl, —

the surly fellow refuses to depart

but scowls back. The irony's on me.

How did I ever get to be you? It's true.

I'll scrabble up some precedents.

Elizabeth used thicker makeup and no mirrors.

The Marschallin stopped all her clocks. But it is vain.

Still comes the day the inner I must eye itself,

the withered frame curls fetal to the wall.

No comfort there. Where are those snows of yesteryear?

Where's Villon? Rossetti? Hell, that was just meant for school.

But Life? An' I pluck this gray hair out, it hurts.

It hurts, and therefore I live. In the sobered eyes

I find something familiar, something

I might own to (though they wince to see themselves),

and even the five-o'clock-shadow face

bears yet some semblance of the serious boy

who still peers out at me from pictures. The lips

of the young poet quivering to recite his love.

The slightly frowning brow that knows all this already.

Here is no surprise then.

Up and doing then.

Much is still unseen, undone. The windows need cleaning.

Outside the February wind awaits, a free, new tousel,

another look, another chance.

Cleaning Up

For Charlotte Elena

Already putting childish things away —

Too soon! my mind cries, though my eyes

smile on you in their accustomed way.

Those are my memories too that you

so blithly pack in cardboard boxes

marked for the attic or the dump —

hideous, pink ponies we rode

together once; garish beads

I saved I know not how oft

from the clutches of the vacuum;

girlish, crayoned Picassos;

dolls you dress up one last time

fastidious as an undertaker.

I have not changed so much

(I cheer myself), but each year

works sea-changes in you, bringing

you taller, wiser, and more beautiful,

and with that strange sensibleness

of youth, you will not sadly look back

but welcome the future where you want to be.

Sandbox, Soldiers

All month now, as green has struggled toward the sky,

they have stood guard, stern soldiers clad in a fading

Union blue. In balmy sun, in day-long showers

they wait, as they have always done, their faces

grim with expectation, their hands clenched

round their weapons. Now some are fallen in the driving wind

and lie with rifles shouldered. A horse lies near them in the sand.

All now incarnadined with blossoms from the redbud,

they lie without a boy to general them around.

Unfazed by time, they wait for small fingers' grip again,

for careless frowns that send them where, though old now,

though stiff and scarred with many weathers, they want to go:

to the cannonaded fields, to death grips, to the fray.

And all but unresentful that the boy in me has long deserted them.

Eight

For Jeffery David

Hurry up, it's late! Hurry up! It's late!

The morning sound repeats insistently amid

the breakfast dishes' clatter, the revving of a car.

Yet shoelaces double-knot themselves with the lazy tempo

of last night's dreams, which seem to hang on you

still while second grade awaits. Hurry up, it's late.

So much seems slow in being eight.

Sometimes, through the glass doors of the porch,

I notice three of you sitting together, gazing

reverently up (as in a church, except you are three boys

and you are eight) at something which I cannot quite see.

The innocent, fresh faces of your “gang”, free now

to play video games without homework, without girls,

trading the latest secrets of your craft with no thoughts

yet of personal glory, debating the arcane rules

earnest as parliamentarians. Or else I watch you swarm,

beelike, the length and breadth of the sideyard soccer field,

your voices mingling in a high choir of delight,

heedless of the chill autumn air or of the coloring sun.

So much seems fast in being eight.

If I only blink, I see you three together still

at sixteen perhaps, “almost grown”, lanky and angular

and with shadow beards. And when I try to listen in

I miss the sweet, soft voices (quite like girls'),

the little hands just large enough to hold or shake;

all the earnest talk of Mario and Lego's been replaced now

by math homework or sportscars, or the school dance

about to start. Hurry up, it's late! Hurry up! It's late!

Sometimes I grope back through the dusty stores

of my own memory, past twenty, past sixteen,

even beyond being eight.

I am six

and quite uneager one night to fall asleep alone.

My father comes to talk with me, sitting by the narrow bed.

I am impatient being six. All good things in life begin at eight:

Cub Scouts and Little League and writing cursive script.

I want a uniform to wear to school and lead the pledge in;

I want a real, felt baseball cap with eight rows

of stitches in the visor. I even want real homework,

to be seen walking from school with inch-thick books

gripped casually at my side. To do these things requires

being eight, and I am six, and much seems slow in being six.

My father listens, smiles. He can remember being six,

and eight. Six is a good age; eight is even better.

It will come, surely. I will dream real dreams about it.

So much seems rushed now, faster than the video days and nights

you summon with a song in Zelda. Generations blur.

Last year you cried at the thought of leaving seven,

but being eight is as good as ever it promised to be,

and having once begun is half-way done now. You want to hurry,

with nine (horseback riding and the “major leagues”) on the horizon,

but even though it's late I'd have you linger

just a little while. So much seems too fast in being eight.

Pinewood Derby

For Jeffery David, and Jeffery, and David

You know, it's really for the fathers after all,

a chance to show off one's tools, one's handiness

at woodworking, one's skills in “shop”. This thought's

no help to me — two left hands when it comes to tools.

I measure twice, but need three cuts at least.

But I have a boy all eager and innocent

of these finer points of fatherly humiliation:

in the end, procrastination will not do.

And so one night we mark our block of wood

and try to cut it with a hacksaw (the only tool

I have that's nearly suitable). The awkward bits

I clean up with a wood file I picked up somewhere.

It whirrs and sends the sawdust flying — voilà.

I try to babble on about the process,

why this tool and not that, why not the one

we have not got, or how, like Michelangelo's

David, the simple block contains it's artifact

already, which we only liberate.

(More filing there might do it!) I think he could

handle the wheels himself, but they must be straight.

He wants to see it go and cannot understand

why I keep taking the wheels on and off again,

and do not let it fly across the room

(as Nature meant) to slam into a wall.

I think he might try, himself, the first coat of paint

(we've chosen royal blue), but it's oil based

and even if I had some turpentine

at hand, I do not relish rubbing his fingers clean.

It's hard explaining that we have to wait now,

that tomorrow I'd better do the finishing coat.

Perhaps, when I find a proper weight, file it,

and weight it out, he might glue it into place.

You see, I've been through this before. An old hand.

My father — artist, woodworker, basement full of tools —

took me in hand to build a thing of beauty,

an old Indy-car, perfectly rounded, aero,

a sleek “ghost gray” with racing stripes in red,

wheels straight, weighted (I see him soldering the lead).

My memory is that we won first prize that day,

the “gray ghost” streaking effortlessly ahead

of every other car, whizzing along the varnished floor

of the school gym toward the finish. Cheers. A trophy.

This year we don't win, indeed don't even show.

The early heats disclose our fatal flaw:

my shiny weight (so cunningly disguised

to seem a turbocharged exhaust) slows us

the moment we're off the ramp on the finishing flat.

Over and over it happens, and toward the end

he doesn't even watch, but plays with friends.

I sit, with a wait-till-next-year smile, front row.

As we drive home, he tries to cheer me up:

“It's still a good car, dad... And I can play with it now.”

The Last Spring of the Millennium

For Jeffery David

It begins with snow: great, wet, transforming flakes,

winter's heavy hand to press and snap

old branches that will never turn to boughs.

The hedges sag with a sudden bloom, the walls

pile high, the early bulbs quite disappear from view.

Even by night we see the tiniest details:

the tracery of branches, pickets, pine needles.

By day, it is blinding in March's shadeless sun,

soft as the air of the blue day first hits 60.

And as quickly gone. The spring has come.

The last spring of the millennium. Will it be

in any particular, in any way

different from the storied springs all poets

celebrate? from troubadours, or Shakespeare?

Wordsworth's glad May or Eliot's cruel April?

Much is the same. Armies prepare spring offensives,

brokers in lightweight suits still watch the Dow,

scientists in sunless labs prepare

the future, lovers haunt shopping malls

to set their wedding registries,

the networks ready for the TV sweeps.

This much is as it might be: life's rhythm

continuing, preparing exams or vacations.

Why should we pause for any spring? and this one?

It's only millennial for us. Not Moslems, Jews.

And what of that Roman who got his dates all wrong?

For anyone who isn't dying now

it hardly seems special, this millennial spring.

Why not let it pass with the thousand others,

its blossoms break unnoticed like mid-ocean waves?

And yet to miss this is simply to miss all.

Not to sense the overwhelming green

lightening wintered hearts, not to watch the spring,

blossom by blossom, in millimeters creep

will be a festering grief. And so with any season.

We go out while the snow still clings

under the northern walls and pine boughs and feel

a fine benignity of the warming air,

the invitation to new life, the primal

energy that has not grown weary with years.

You've known but eight springs of these thousand,

yet you sense it. “Dad, I see an angel's blossom.”

I'm not sure what an angel's blossom is,

but it must be good, all full of April

and the spring, this feeling that propels us

to outgrow ourselves as the blossom its bud and bole,

to put on our best white, wingling as angels do,

to live together the young season under the old sun.

Watching for Snow

For Charlotte Elena, Age 16, January 2, 1999

Was it just steam filling the radiator?

Or had the snow begun, millions of crystals

pouring from heaven, dancing at the windowpanes?

No matter. We watched, for perhaps the dozenth time,

our old tape of the Kirov Swan Lake, scratchily

monaural, clumsily filmed with static camera shots,

bewitching. And you were caught once more,

your six years slave to Rothbart's trance, and I,

a prince again, would rescue you, lifting you

high in the air, turning you this way, then that,

your arms aflutter as the desperate, last fight

filled our small room. Over and over we played this.

The music swelled at us in dangerous appassionato,

yet in my arms you were but featherlight

and the vague, painted evil haunting the little screen

would stand no chance against us.

Now you've awakened, swanlike, to sixteen years

that watch you wear out pointe shoes on real stages

where Princes and young Rothbarts alternate their parts,

where ills and evils haunt backstage and audience-dark.

And you arch over them with practiced relevés,

with arms extended, waving, and with determined gaze,

and still I ache for you at every leap or turn.

I watch though I no longer lift you above the fray.

Are the predictions right? will it snow now after all?

or is it simply grim with wind and hail and rain?

We wait, uncertain yet, searching together the dark

windowpane for signs: a distant glimmer in some outside

light, a telltale tapping of the crystal

dancing flakes, and as I watch you poise now,

ready to leap into whatever scenes will come

when the glass shall brighten with revealing day.

Aspiring to the Condition of Espresso

Although it's technically French roast, we like

our coffee finely ground and strong, aspiring

as it were, always to the condition of espresso,

so strong in fact it frightens our visitors.

We'll make it at night and set the timer going,

so that we wake to the sound of steaming water,

the smell of coffee wafting through the house.

You'll have your cups con latte, while mine are black,

sweetened just so to drive the edge off bitterness.

It's always been this way, for me at least

since I was a teen too young to know better.

Alone much of the time, I got somehow

the habit of visiting my grandmother each day.

Mornings I'd set off as purposeful as if

there really was someplace I had to be,

walking the three blocks to her snug, brick house.

I can still see the kitchen, thick plaster walls

bright with old fashioned, painted cabinets.

I can still smell Italian specialties

already started cooking on the stove, steaming

from odd-shaped, much-used pots or pans. Sometimes

there would be peppers frying right on the fire,

their bright colors blackening before my eyes.

Even now I smell them, an indelible deliciousness

filling my memory as it once filled that room.

Back then I worked at pronouncing the funny names:

osso buco, strufoli, or something cacciatore.

Our talks were laced with Italian I'd sense and feel

if not always understand. It was always something different:

the Italy of her youth, her wondrous sense

that the earth moved on her first train ride to Naples,

her youthful sadness at the news of Rei Umberto's death,

the woman from her village who pretended to read

only to be caught holding her book upside-down:

“Stupido, don't you know all the best people read this way?”

I used to write translations of her proverbs:

“The habit does not make the monk,” of course;

yet in the next breath “Clothes do make the baron.”

“The head that does not think becomes a squash.”

“Aspetti cavallo, wait horse, the grass will grow.”

Of course there were many stories of her father,

the country doctor who fought with Garibaldi,

sang in the church choir only to meet the woman

he made his wife, who played the flute and wept

when having lost a tooth to age he could no longer play;

the story of her first trip far from home,

a visit to America that somehow never ended.

And there were her dreams, mystical premonishings

of her father's death, of her children being born;

one where she called out to my father who walked right past her.

All this with a candor innocent of my youth.

We sat together at the old, formica table

day after day, always sipping espresso.

I was too young, of course, for coffee at home,

but she never blinked at getting out the funny

old pot that looked like two pots stuck together,

the little spoons and cups almost like dolls' china,

where even so the coffee was so dark we could not see

the grains gathered at the bottom — like the future

soon to happen and before which we quietly paused.

Traveling from Virginia by Train

We all age together, this one day at least.

The grandmother traveling for her birthday party

in a place once home, the students heading back

after a semester's “grown-up” freedom, the young woman

whose children trail after her like ducklings

on the way to the dining car. And I, the weary one

longing as well for a bed at home, the watchful one

feeling my beard grow in the silent pauses.

The conductors, old hands at scenes like this,

read us all and smile and offer practiced chat

as they near the end of their “run”. As always,

there are glitches and delays, but only the young fellow

with a plane to catch seems anxious to banish the hours.

The rest let the day pass, moment by moment as we must,

in a sort of quiet benignity, keeping our public poses

and our private thoughts, keeping a stillness as if

oblivious of the rattling, vast machine that rushes us

each to his destination.

Kampf

For Professor Edward Glas

Oh, how you'd have gloried in this foolish war!

There you'd be again, up at the blackboard tracing

the Ottoman and Habsburg roots, explaining in precise

detail just why and how they hate each other,

have done from Time immemorial, will always do.

You predicted it, of course, way back when:

As soon as Tito goes, just watch... I know.

I heard you. I still do. The voice returns now.

When we first learned you'd died (one dreary Sunday

otherwise quite ordinary, drizzly, dull,

spread with the New York Times) it seemed almost

impossible. I could still picture you a hundred ways:

the mock-fierce, Prussian eyes that would light up

suddenly in ironic smiles, the “famous” stance

at the lectern, a cigarette in one hand, coffee

in the other. Habsburgs and Hohenzollerns

crowding each other on the blackboard, more real

than the fatuous importunings of provosts or deans.

Dreikaiserbunds and Zollvereins, Moltke's

“best poetry”, Graf von Schlieffen's sleeve,

and Bismarck's “damn stupid” Balkan quarrel

(There are some problems that may be insoluble),

Metternich, Napoleon, Andrássy, Wilhelm — so much

life in that modulating, flickering tongue.

I'm always there as well, the eager, admiring

student whom you'd coaxed from painful isolation,

transformed to the dignity of Einsamkeit

(What the Germans mean when they talk of Einsamkeit

is more than just our loneliness or solitude),

mentored out of loony adolescence,

guided surely toward the grown-up life of the mind,

tough but sensible: Ha! Mr. Triggs,

do you know why I'm arguing this point with you?

I want to teach you to be an intelligent conservative.

On learning that I'd switched from history to English:

So, you're going over now to the soft side.

That's OK, as long as you don't go too far.

Now, barely mezzo del cammin, so much gone with you.

All through that Sunday I struggled to keep hold of the voice,

but it seemed the first to go, crumbling away

with each soft touch of the imagination.

Realpolitik, that good psychologist,

means putting such things safely out of mind.

There were, after all, other things to do.

I had my own life on the wing now as it were.

I had that Ph.D. to finish, which you knew

would be for me a Kampf, a desperate struggle.

Over a shot of booze one night: you know,

this is one of those things you'll have to tough your way through.

A long haul — and then you can write your poetry.

I toughed and hauled, and how easy it was to forget.

Just as my life, with such guidance, took its flight,

you crashed, lonely, graceless, untenured, appalling:

court fights, asylum time, whiskey at eight in the morning

to help tough through. Some problems are insoluble.

And where I could not help, I mostly winced away

like the others with life still to get about.

terrified now to touch that glowing, searing,

still-living thing, your solitary pain.

There were, after all, so many things to do.

Strange, I am older now than you ever were,

venturing the uncharted future on my own,

free to think thoughts of sober coloring,

to make of the facts what I will, and at last,

in the glow of civilizing sense, quietly,

simply, gratefully to remember you.

III. Detail of the Last Judgment

A Visit to the Museum

Entering the gallery of the dead, you feel

a hush of life, as in a church. Rising up flights

of granite steps out of the traffic, out of affairs,

you enter the quiet precincts of past centuries

and their peoples. Fashions change. Scenes change.

Time itself seems to wobble in these halls.

No matter how quietly you try to go, on marble floors

your shoes scuff or squeak and wake the thousand ghosts

who peer at you from their places on the walls,

each, like Francesca, with a story to be told.

And sometimes, as in church, you may almost come

out of yourself (that daily prison of the senses),

out of the strict confinement of each moment

hurtling you towards death. Here death’s all around,

like a great freedom, and natural as a different life.

Edvard Munch — The Shriek 1910

Is there no one here to ask:

who is this who has lost his way

among unlistening stars?

All the body is pure sound

bursting from its edges

echoing back merely upon itself.

He has released the undulant world

like a womb.

This is the only shape such terror knows,

all contortion of flesh,

all noise—

helpless as a whisper against eternity.

Paul Delaroche — The Execution of Lady Jane Grey For Charlotte Elena

All are in place: the weeping servant girls

who cannot bear to look, the ministering priest,

the patient executioner with polished blade

ready in hand, the venerable oak block

contrasting strangely with the one-day straw.

And Lady Jane herself, blindfolded, terrified,

her brief seeing in the complicated world

already done, kneels with her best satin gown

drawn to a murderous décolleté.

The artist has delighted in the clash of textures here:

satin and steel, velvet and burnished wood,

straw and the poor girl's length of red-gold hair

so soon to be incarnadined. Another bride to death.

Others pass blithely by this scene, but you, my little one,

bring to it your four year old passionate stare,

an innocence, like hers, confronting death

(which even wise ones can't explain) as by necessity,

and a regard of love to span the blank centuries

hanging suspended where the servants dare not look.

Willem Kalf — Still-Life with the Drinking Horn of the St. Sebastian Archers’ Guild

Like most still-lifes, it speaks to us of death.

A banquet stays on to mock the departed guest,

the diner called suddenly from his table.

In his absence, we peruse the careful setting: silver plate,

a crystal goblet and decanter filled with sherry,

a tawny drinking horn with rims and stand

carefully worked in silver, and hastily dishevelled,

its patterns bunched and overlapping, a rich fabric

of the orient. Uneaten delicacies — lobster and peeled lemon,

cheese and wine — tease us, so that our living mouths water

at what has turned long centuries ago to dust.

Against such appetite, the sensible mind repeats

memento mori, nothing persists; though in Holland

it may be the emptied horn is still displayed.

Whistler — The Little White Girl: Symphony in White, #2 — 1864

In the old religious allegories

mortality is hidden away. The face of Mary smiles her

eternal smile; Jesus continuously beams.

In portraits like this, though the artist emphasize

the harmony of his paints, we see a human face

meshed in its emotions and in time.

And so the white girl with her frills and wistful eyes

is very much of her moment, like the flowers

(put here for contrast) with their week-long bloom,

and in the mirroring of her face a melancholy look

speaks of its certain dissolution. This is still-life too.

The flowers, the fan, the dress, the girl:

in a rushing multitude of minutes all are

all were already sweeping to oblivion.

With our own century still warm about us,

we peer at the cool, painted images of hers.

Deathmask of a Girl Drowned in Paris — 1895

About the forehead only a slight grimace

speaks of something human, something flawed.

The mouth large, open like a kiss.

The eyes tightly closed, as if she were

a saint seeing God in the darkness.

The cheeks hard and smooth, like stone

water has polished for an eternity.

Did someone really live in this face?

Attic Stele on a Child's Tomb

Now that earth has recovered

from the wound inflicted by her grave,

she will appease the day's blue yearnings

with a journey, her casual eye

pausing in the usual, the well-worn places,

casting about for the flesh of memory.

Out of Chthonic depths she brings a smile

through centuries of youth, through all

the deep imaginings of spring, into

this warmth of stone. There she rests,

waiting in her smile like a kiss.

The Lacemaker Ca 1666

The light as usual enters from her left

To fill the almost empty room;

Her hands, practiced, meticulous, and deft,

Attend the rich laces on her loom.

In detailed miniature she pours her fine

Devotion, soul, and female heart.

Her eyes, like Milton's, someday may go blind

From the long peering of her art.

John Brett — The Stonebreaker — 1857-58

He is younger even than his morning

spread with such soft, early light,

purpled with miles of distance,

wild-flowered and blue-skyed.

He wonders, bending with his mallet,

are there times when there aren't any hours,

times made of Sunday afternoons,

times made of meadows and wild-flowers?

But today the great rocks have yet to grow little

(as they must), and though the dog would play,

he bends disconsolately to his task,

the consummation of his day.

Behind him, a robin perches on a tree-stump;

before him, like bones haruspically tossed,

the broken knuckles of the stones:

the future where his gaze is lost.

Hughes — April Love — 1855-56

She is not one to be taken, some midsummer's

night, under a hedge, but still, in her ivied bower

strewn with a first fall of lilac-colored blossoms,

she requires discretion. While she looks outward to the light,

her lover kneels behind in shadow, as natural

as the green, blossomed background of his furtive kiss.

A kiss of nature. And she yields to it

uncertainly, her hand at first, and what sensations

thrill her we may only guess, as whether she will flee

next moment into the sunlight that strokes

her cheek and hair and arm and the blue folds

of her dress, or turn from us to his soft shadowy

caress.

Rossetti — The Girlhood of Virgin Mary — 1848

Of Rossetti’s model here we know too much

to let her pass in legend with its leavening

of mortality; not so much Mary as Elizabeth,

and we know the gruesome circumstance of her death.

And so we view, in a kind of double vision,

the real girl with her waist-length, golden hair,

her hand-work, and her chaste Victorian dress,

set among angels and symbols: the palm, the lily,

the dove, the rose, and visible through the trellis

holy land. Her face, haloed and intense,

holds something back, as if she stored up strength

for the great role before her now, and as we guess

the lustrous, secular play of her few mortal years.

Gainsborough — Giovanna Baccelli — 1782

Gainsborough put her in that abstract land,

Arcadia, and set her dancing to a shepherd's flute

(his timbrel lies nearby), ribboned her dress

with colors of the sky, and strew her path with roses.

But something in her blushing cheeks, and the smile,

delicate and Italianate, on her lips and eyes,

tells that she won't stay framed in Arcady for long.

She is no pale nymph, but a woman whose passion

is for the world of days and weathers, of momentary

musics, roses blowing and blown. For her

mere mortal loves suffice, all preparations and regrets

at which she smiles her sly, sweet, knowing smile.

Gainsborough — The Housemaid 1782–86

Posed with her broom, all sepia and pink,

she stands in a rustic doorway. On her face

the familiar longing directs her glance outward

to a vast, unpossessable world, or simply

to this close room with its aristocracy of ghosts.

Perhaps, she feels the urge to turn within,

having seen enough, for surely she’s uncomfortable

with the likes of Giovanna Baccelli

or the young, dead lord who poses on the opposite wall.

Yet her beauty, simple and delicate and human,

transcends the meanness of her class, and dominates

the long years more surely than the satisfied smug looks

of those who paid their “immortality” in full.

Sargent — Lord Ribblesdale — 1902

As emblems of his class, he poses with

polished boots, silk top-hat, a silver handled

riding crop, and of course an arrogant gaze

meant to suggest the generations of his breeding.

The background, too, is elegant and old,

a parquet floor and fluted molding in the “classic”

style. This is the style of the world he lives and owns in,

the belle epoch that was surely vanishing, even

as he hung its image here, monument to posterity

and self, this expensive portrait

gawked at by commoners of the future.

Sargent — Ena and Betty, Daughters of Asher and Mrs Wertheimer — 1901

Ena and Betty, both statuesque and pretty,

peer at us from their frame among their paintings

and their objets d’art with such delight

that it seems nothing but good fellowship.

Seeing them thus, Ena in red velvet evening dress,

Betty in white silk, both dressed to the nines,

one hesitates to imagine what dark times

the still fresh century brought them. No.

Let’s not detain them from the dinner that awaits

to linger dryasdust with indigestible thoughts,

but wave hello, goodbye, remembering their young smiles.

Sargent — Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose — 1885-86

The elements of this painting mesh so well

that there seems little to say, but to remark

Dorothy and Polly lighting lanterns in their garden

in Broadway, in summer, in twilight, innocent.

Surrounding them, to set off their innocence,