For the Polish people, Shakespeare’s Hamlet is by far the best introduction to the dramatist’s entire body of work.1

As the eminent Neo-Romantic Polish painter, poet and dramatist, Stanislaw Wyspiański (1869-1907) has said: “In Poland the puzzle of Hamlet means: everything that is in Poland to think about” (1961: 99-100).2

Wyspiański’s succinct observation conveys the essence of the Polish appropriation of the play. In fact, the very character of Hamlet is very often described as “the Polish Prince,” and he is regarded as a significant figure in Polish culture. It is as if the play had been written for the Poles, and it serves as an amazingly functional vehicle to break down any presumed cultural barriers between Polish audiences and the works of a master British playwright.

Hamlet appears to support the dramatist’s knowledge, or at least awareness, of Poland. In the play Poland and Norway provide the European background of international politics, the verse “the sledded Polacks on the ice” (1.1.66) makes the reference to heavy Polish winters, while the English translation of Goślicki’s De optimo Senatore was probably, as Teresa Baluk points out, the source of “Polonius” (“Polish” in Latin).3

In 1956 Witold Chwalewik wrote his controversial monograph Polska w “Hamlecie” [Poland in “Hamlet”], a profound textual analysis of echoes of the Polish Renaissance apparently present in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Later in his article, “The Legend of the King Popiel: A Possible Polish Source of Hamlet,” Chwalewik pushed his idea further, stating that Hamlet was, in fact, based on the fusion of two sources: the Danish—the first nine books on the Danish History of Saxo-Grammaticus, and the Polish—the semi-legendary story on King Popiel eaten by mice that a Polish and many popular European chronicles reprinted in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (1965: 99-126). Although Chwalewik himself was aware that much of the evidence he presented in his monograph and in his essay was “surely [...] a wild fancy” (1965: 115), his work was a significant and meaningful venture—an attempt to appropriate Hamlet for the propagation of Polish history and culture at the grim time of Communist regime (Kujawińska Courtney 2001: 52). Hamlet, indeed, served this purpose, not only in the Communist context. Actually, since its first appearance in Poland, it became a medium through which actors, directors, translators and critics tried to voice their concerns and deal with problems of their contemporary Poland.

The national interpretation shows three traditions of responding to Hamlet in Poland. Theatrical stagings and criticism have tended to treat the original text as a convenient commentary upon current political and social experiences and dilemmas. Creative and literary response have been inclined to remake the myth of Hamlet as the archetype of a Pole entangled in the fight for the national cause. Common reworkings of the play reflect Polish national mentality, complexes, inhibitions, obsessions, and inclinations.

The text of the play, understood in the literal sense, found its way onto Polish soil relatively early. Its seventh extant copy, in the Second Quarto edition of 1605, was brought to Poland by Karel of Zerotin [Karel starsi ze Zerotina] (1564-1636), a Moravian nobleman, who had purchased it in England. After the White Mountain defeat (1620), Zerotin, the leader of the anti-Austrian party of the Moravian gentry and the representative of non-Catholic nobility, moved to Wrocław (Breslau) in Silesia. This is where the copy found its permanent home in the University Library.

Since this copy was found only in 1950 by Professor Juliusz Krzyżanowski, one of the most eminent Polish literary scholars4

, and since no mention of the play can be found in Polish documents from the seventeenth century, it seems unlikely that Hamlet was known to the Polish public at that time. The first documented reference to the play appeared in 1778, when Piotr Dufour, a Warsaw book-store owner and a publisher of academic works and foreign literary works, advertised in a local newspaper the Schröder adaptation. His advertisement gives a critical outline of the play, stressing for publicity reasons its sensational elements (Komorowski 1992: 100).

As Marta Gibińska rightly observes, Shakespeare in Poland, or at least the earliest Shakespeare in Poland, is Shakespeare in theater (Gibińska et al. 2003: 46). The first theatrical renderings of Shakespeare’s plays in Poland were given by English strolling troupes of players visiting northern and central Poland. It is possible, as Jerzy Limon maintains in his monograph Gentlemen of A Company, that these visits are related to the fact that the only known example of Elizabethan theater operating on the Continent was located at the Baltic Sea, in Gdańsk. Built in 1610 and resembling the London Fortune Theater (1600), Gdańsk theater—called Fencing School (Fechtschule)—provided a multipurpose space: it was used for fencing competitions, animals fight, shows of jugglers and acrobats, and theatrical performances. One such troupe of “English comedians,” under the direction of John Greene, performed in 1616, 1617, and 1619 at the court of King Sigismund III Vasa (1566-1632). Later English traveling troupes were welcome by Władysław IV Vasa (1595–1648), a connoisseur of the arts and music, who created the first amphitheater in the Warsaw castle (Limon 1985 and Stribrny 2000).5

As the documents demonstrate Hamlet found its way into their repertory only in 1626 (Limon 1985: 22). Like other Shakespeare’s plays, it arrived in a simplified original form or translated into simple German. Thus, the general Polish public began its acquaintance with Hamlet through a culturally alien prism of foreign languages and interpretations. This situation continued in the Enlightenment when Shakespeare—practically absent on Polish stages from the Swedish invasion and occupation (1655-1660) till the end of the eighteenth century—was still treated as the cultural “Other.”6

The eighteenth-century Hamlet was shown mainly in performances by German theatrical troupes, who visited Gdańsk (1775), Warsaw (1781), Lvov (1796), and Cracow (1797), staging the Schröder adaptation of the play in German.

Hamlet’s “proper” entry into Polish culture is associated with the Polish Enlightenment and the activities of the Father of Polish Theater, Wojciech Bogusławski (1757-1829), an actor, playwright and theater director. Known for creating a national theater and spreading patriotic ideals, Bogusławski actually introduced Shakespeare to the Polish stage. His work falls during the period of the partitions of Poland, i.e. three territorial divisions of the country (1772, 1793, 1795) perpetrated by Russia, Prussia, and Habsburg Austria. After the final partition Poland disappeared from the map of Europe. Thus, the social and political importance of Bogusławski’s theater was enormous. He considered theater a space for maintaining and cultivating patriotic feelings and hope for independence. In 1794, after the Kościuszko Insurrection failed, Bogusławski left Warsaw and a year later started his activities on the stage in Lvov, a Polish town. There on April 4, 1798 Hamlet was for the first time staged in Polish, in Bogusławski’s own translation and interpretation of the German versions by Friedrich Ludwig Schröder (1744-1816) and August Wilhelm von Schlegel (1776-1845). Although Bogusławski’s stagings of the play were in Polish which was a benefit to his audience, his Hamlet cannot be said to serve the original well because it was presented in a pseudo-classical guise. In “Uwagi nad Hamletem” [Remarks upon Hamlet], attached to his version of the play, he justified his treatment of the original:

[I]gnoring the dramatic rules by the introduction of secondary events which destroy the unity of the action, [Shakespeare’s play] murders the listener’s mind by introducing on the stage indecent people and repulsive sights, lowering the dignity of tragedy. In its denouement it misses the moral point, punishing with death also the innocent. In a more enlightened age it could be neither staged without a decent correction nor completely forgotten because of its other, undeniable beauties, which only Shakespeare’s genius could create and mark with the feature of immortality. (qtd. Helsztyński 1955: lxxxvi)

Thus, following his belief that Hamlet without corrections cannot be presented in the age of Enlightenment, Bogusławski introduced many changes. He cut out the grave-diggers’ scene. Fortinbras disappeared as apparently not connected with the main plot. Hamlet did not go to England, because this trip destroyed the unity of time and place. He was not killed in the duel, because he was not guilty as Claudius was. For a better tragic effect Ophelia's death was preserved, Hamlet and Laertes shook hands in reconciled friendship over Claudius's body [fig.1]

.7

|

| [fig.1] |

|---|

In this context, Bogusławski’s ending of the play can be regarded as the beginning of Polish cultural appropriation; when Hamlet as the legal ruler ascended the Danish throne, the servants on their knees begged Hamlet for forgiveness because of their previous disloyalty. Since Bogusławski is known as a patriotic writer,8

it is possible that this unusual denouement was prompted by contemporary political events in Poland, if not directly, then by analogy, and made a direct comment upon the current Polish situation.9

The first Polish staging of Hamlet coincided with the defeat of the Kościuszko’s Uprising in 1794, the third and final partition of Poland in 1795 and the death of the last Polish king, Stanisław August Poniatowski, in Russian exile in 1795 (Kurek 1999: 9-40). Thus, such an alteration of the play could have been introduced purposefully to remind the public of their allegiance to the Polish crown and to Polish statehood. Bogusławski’s Hamlet was so overwhelmed with political issues that he was unable to act. Yet, as the rightful heir to the throne, the Prince had to punish the usurper and restore the original order of the world destroyed by the crime. In Bogusławski’s production social and political issues became responsible for Hamlet's spiritual irresolution, while the transcendent dimension of the tragedy assumed secondary importance.

The frequency of the revivals of his adaptation confirms Bogusławski’s opinion that it was a great theatrical success. He staged the play for example in Vilnus (1808), in Cracow (1817), in Kamień Pomorski (1821), in Human (1827) as well as in a Polish theater in Kiev (1816). In his notes on the history of the national Polish theater, Bogusławski wrote:

This tragedy, produced for the first time in our native tongue in 1797 in Lvov, made a great and varied impression, and because of its success with the public, was repeated several times. The unforgettable [Kazimierz] Owsiński in the role of Claudius and [Franciszka] Pierożyńska as Ophelia, particularly in the mad-scenes, acted enchantingly (qtd. Helsztyński 1955: lxxxvi).

Typical for his times, in these performances Bogusławski played not only the title-role, but also the role of the director/manager of the troupe, and the role of the repertory's critic.

Żurowski refers to Bogusławski’s Hamlet—the first incarnation of Polish Hamlet—as a “pre-November Hamlet,” making reference to the November Uprising (1830), the first significant turning point of Polish culture in the nineteenth century. This Polish pre-November Hamlet emerged from various French (Ducis, Le Tourneur) and German (Heufeld, Schröder) adaptations, following the changes of the eighteenth century theater (1976: 232-4). Yet, Polish pre-November Hamlet meant not only Bogusławski’s adaptation. Actually, though Bogusławski introduced Hamlet on the Polish stage, it was Jan Nepomucen Kamiński (1777-1855) who developed it.

Kamiński, who based his adaptation of the play on the Schröder’s version of 1778, provided a new perspective on Hamlet, as well as an opportunity for new theatrical aesthetics and new staging solutions. First presented in Kamieniec (1805) and then for many years staged in Lvov, the Hamlet text is subordinate to his theatrical vision—which means that practicability onstage takes precedence , and the text is just a building agent, a tool for creating theater. Although Kamiński tried to stick to the elements of conventional rhetoric, his Hamlet, with its sentimental accents, more dynamic text and the literary means to express tensions and emotions, introduced a new aesthetic orientation—romanticism. As Żurowski asserts, Kamiński’s Hamlet followed Bogusławski’s solutions in terms of plot: omits the duel, leaves the just alive and makes the guilty die. At the same time, it connected pre-romantic sentimental with gruesome stories, and thus “co-created the intellectual formation of the theater of its times” (Żurowski 1976: 244-5, 249-51).

Both productions of Hamlet, Bogusławski’s and Kamiński’s, turned out to be very influential in shaping the Polish reception of Shakespeare in general, but also in marking out the direction for the Polish incarnation of the play. On their basis still another pre-November Hamlet, an anonymous script now kept in the Ossoliński Library in Wrocław, was created: Hamlet Królewicz Duński. Trajedyja w 5 aktach Szekspira. Its author referred to Schröder’s version, but also directly and to a large extent used Bogusławski’s and Kamiński’s texts.

The beginnings of theatrical criticism can be associated, according to Żurowski, with the introduction of a permanent theatrical review section in Gazeta Warszawska in 1802 (1976: 32). The critical approaches of that time applied the criteria of classicism to the staged plays, and most of the reviews drew heavily on the opinions of French critics. Thus, the Warsaw production of Hamlet, reviewed in Gazeta Warszawska in 1812, was evaluated in comparison to classic tragedy and criticized for the fact that “such a great philosopher as Hamlet is very afraid of spirits and ghosts and sees them so often” (qtd. Żurowski 1976: 32).

In spite of this criticism, Shakespeare’s play became very popular with audiences, satisfying—as many reviewers believed—their bad taste. Later reviews, however, show that Hamlet underwent general transformations and was indeed affected by the changing tendencies on Warsaw stages. Emphasizing the elements of menace and the value of expression, and approaching the play mainly from the perspective of sensationalism and supernatural elements, the review of 1816 states that “Hamlet [...], who has just seen the ghost of his father, still fully imagining this terrible occurrence, [...] wherever he turns he can hear this ghastly voice” calling for revenge (qtd. Lipiński 1956: 167). Although the Polish theater audience wanted to have—and indeed had, as the above mentioned productions prove—a Hamlet that is “more real and more suited to his time,” pre-November theorists and critics had a different Hamlet on their minds, or rather a “myth of Hamlet—a medium of Romantic ideology” (Żurowski 1976: 255-6).

The critical reception of Hamlet, as well as the critical reception of Shakespeare in Poland, followed a slightly different path than the theatrical renditions of his plays. It goes back to the second phase of the development of the Polish Enlightenment, when Stanisław II August Poniatowski (1732-1798) help found the Polish national theater and when Monitor, the leading periodical of Polish Enlightenment, published Ignacy Krasicki’s (pseudonym Teatralski) biographical and critical information on Shakespeare (following Dr. Johnson’s ideas).

Although in eighteenth-century Poland Shakespeare was not counted among respectable writers, sentimental worship of cultural heritage and the cult of an author fashionable at that time did influence Polish perception of the playwright. Close connections to English literature are established by Poniatowski himself and by Izabela Czartoryska (1746-1835) for whom “reading” Shakespeare meant, apart from examining the texts, visits to Stratford, to the galleries and to other places that invoked locus geni.10

The Neo-classicists’ dogmas were entirely rejected when the first tide of Romanticism reached Poland at the end of the 1820s. Nevertheless, Shakespeare's works had to wait for the full tide of Romanticism to reach Poland before they could appear in an authentic form, translated neither from French nor from German versions, but from the original.11

The universal and enthusiastic admiration of Shakespeare shared by the Romantic poets of Poland, themselves striving with passion and energy not only against foreign cultural domination but also against the rule of classicism, failed at first to produce any good translations. Yet this was the time when Shakespeare began his lasting reign in Polish belles-lettres. Maurycy Mochnacki (1804-1834) was one of the first Polish Romantics who advocated an interest in Shakespeare's drama, he revealed the inadequacy of the eighteenth century translations/adaptation, and urged Polish actors, directors, playwrights, and poets to return to the original version of Shakespeare's plays. Maurycy Mochnacki (1804-1834), one of the first Polish Romantics who advocated an interest in Shakespeare's drama, revealed the inadequacy of the eighteenth-century translations/adaptation and urged Polish actors, directors, playwrights, and poets to return to the original version of Shakespeare’s plays.

By that time the “myth of Hamlet—the transmitter of romantic ideology” turned out to be very enduring. The play assumed a crucial role in the birth and propagation of Romantic ideas in Polish culture and its political agenda: the liberation of Poland from foreign domination. Czesław Miłosz rightly maintains that “Romanticism in Poland acquired an extremely activist character” (1986: 201) and the play was appropriated by the Polish Romantics as their poetic manifesto. Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855), the most eminent Polish Romantic poet and one of the most charismatic Romantic warriors against the oppressing Empires, opened his collection of works entitled Poezja [Poetry, 1822], with the poem “Romantyczność” [Romanticism] which he preceded with a paraphrase from Hamlet: “I see. Where? In my mind’s eye.” Deftly expressing the core of the Romantic theory of cognition, the quotation became the quintessential declaration of Polish Romanticism, while the play itself found its numerous echoes in the theoretical and practical foundations of the best of the Polish Romantic traditions.

Quotations from Hamlet preceded other important works of the Romantic period: Adam Mickiewicz’s play Dziady, część II [The Forefather’s Eve, Part II, 1823), Zygmunt Krasiński’s play Nie-Boska Komedia [The Undivine Comedy, 1835], Stefan Garczyński's play Wacława dzieje [Wacław’s Story, 1832], Cyprian Norwid’s poems: “Moja piosenka” [My Song] and “Fraszka” [An Epigram]. Norwid also used the monologue “to be or not to be” in his play Aktor [Actor]. The quotation: “There are more things in heaven and earth, [...] than are dreamt of in your philosophy” was used by Antoni Malczewski in his authorial note to Maria (1825), an acclaimed play. Grażyna Halkiewicz-Sojak demonstrates how these lines acquired an independent existence in Polish literature of the Romantic period when used as epigraphs, quotations and paraphrases in various works (1998: 99-107).

Juliusz Słowacki, another revered Polish Romantic poet and dramatist, was probably the author most strongly affected by Hamlet.12

Słowacki came under the spell of Shakespeare quite early in his life. In the preface to his third volume of poetry, he acknowledged Shakespeare as the greatest poet in the world, better than Byron, Goethe, Dante, Calderon

because not only his heart, not only the thoughts of his time, but all human hearts and thoughts, independent from this epoch filled with prejudices, he [Shakespeare] painted and created with his power similar to the power of God. (qtd. Windakiewicz 1910: 80)

Słowacki’s interest in Shakespeare influenced his own dramatic output. In fact, the Polish poet appealed to Shakespeare as his Muse, seeking a model to follow in his transcendent values. As Witold Ostrowski proves, Słowacki’s knowledge of the English language was crucial in his appreciation of Shakespeare’s work (1964: 131-42). His admiration of Shakespeare is shown in everything he wrote. He was so much in love with the English playwright that out of his fantastic and enigmatic spirit, he wove visions of him as a Pole.13 With time Słowacki’s profound studies of Shakespeare’s works and his own dramatic talent helped him to create one of the best Polish Romantic dramas (Horsztyński, 1835), written after the manner of Shakespeare.

Many of Słowacki’s dramatic works carry motifs from Hamlet. One can be found in his youthful drama Mindowe (1833), where mentally disturbed Aldona delivers a speech on her wreath made out of rosemary and other flowers, and Lutuwer recalls a gravedigger who was singing while digging a grave. In his famous play Kordian (1834) the titular hero repeats after Hamlet: “Now it is the time to vigorously measure the life of a youth, and solve the question: to live or not to live?” However, the drama Horsztyński constitutes the most perfect example of Polish Romantic rendering of the English model. In that play the dilemma of the main character Szczęsny Kossakowski is similar to that of Shakespeare's prototype, though Słowacki’s drama is a fully-fledged political, nationalist reading of the play. Shakespeare’s “family” conflict was given a patriotic coloring. In Horsztyński the main character must choose between his love for his father—a political traitor—and his love for his motherland. The play has also some other parallels: sending the character's mistress Amelia to the nunnery, the appearance of the Shadow (Ghost) of his father, and Szczęsny’s soliloquy, almost a paraphrase of Shakespeare’s “To be or not to be.”

It was in this period that Hamlet became directly implicated in the Polish national cause. In his anonymous article “Być albo nie być” (“To Be or Not to Be”) published two months after the unsuccessful November Uprising (1831), Maurycy Mochnacki announced:

This excerpt [“to be or not to be”] from Shakespeare's poem is to be from now on the emblem of the Patriotic Society. We have also taken it as the emblem of our journal. This quotation expresses comprehensively the gist of our comprehension of the matter and the basis of our politics [...]. Only Shakespearean to be or not to be will save us. There is no middle between these two extremes. (1987: 424, 428)

In 1848 Zygmunt Krasiński, who was against the bloody events of the Spring of the Nations, commented full of anger to his friend:

And here Fortinbras will come, he will come at the end of the fifth act, and he will find Hamlet’s corpse stretched out, the real Hamlet, who [...] has never done anything, except that he has killed one or two people, and next he has died, and he has lost the crown of his Motherland, and here he is lying stretched out, and Fortinbras comes, and he orders men to bury him and he takes his legacy [...]. All of you are like Hamlet! Because you have not taken the side of Christ and Poland—but you have gone to the schools in Wittenberg and have learnt, and learnt at last how to die! (qtd. Komorowski 1992: 115-16)

Hamlet and his famous question: “To be or not to be” became Polish because the Poles understood it as a burning political and moral issue: “To fight or not to fight” for the country’s independence. Tomasz Łubieński, for example, emphasized the importance of the dilemma for the Polish nation in his book on the history of Polish national uprisings, Bić się czy nie bić. O polskich powstaniach [To Fight or not to Fight: On Polish Uprisings, 1978]. The problem “To fight or not to fight” assumed an entirely symbolic and even metaphorical dimension for many generations of Polish people. No wonder, since Hamlet’s entrance into Polish culture coincided with the loss of the country’s autonomy for a very long time: the onset of the Romantic period marks the disappearance of Poland from the map of Europe for almost one hundred years, followed by a brief interval of independence between the two world wars, a virtual eradication of the nation during World War II, and over forty years of subordination to the Soviet Empire. The repressed and marginalized Polish nation began to appropriate the play as an intrinsically and essentially subversive tool directed against the suffocating foreign hegemony. Claudius's repressive and illegitimate reign was to stand for the oppressors of Poland, while Hamlet was, of course, the Polish people. The popularity of the play increased in the times of any political instability of the country.

In Polski Hamlet. Kłopoty z działaniem [Polish Hamlet. Problems With Acting, 1988] Jacek Trznadel extended the myth of Hamlet to the whole historic fate of the Polish nation commencing with Romanticism and finishing with the twentieth century. This interesting and controversial work concludes that

[t]he myth of Polish Hamlet testifies not only about the vitality of Shakespeare in the culture of this society. It is also—beginning from the partitions—the vitality of a certain idea and the ethos of a hero, who wants to act, even in the most difficult conditions, in the name of truth and justice. (Trznadel 1988: 310)

The Romantic period began the mode of response to Hamlet as if it had been written especially for the Poles. From then on, the play was seen to be specifically about the Polish predicament: about the life and death struggle of the nation for survival, about the antagonism between the oppressors and a Poland compelled by faith to play for the highest political stakes, about the conflict created by children's duty to their parents and their duty as patriots, about the tragic inner struggles caused by conflicting emotions like passionate love and hate, about dreams of great deeds and Hamlet-like inability to carry them out, about the problem of leadership and the ethical complications inseparably connected with it. Hamlet himself became an epitome of the weakness of an average representative of the Polish nation who stood helpless before the task forced upon him/her by life, for while endowed with rich imagination and penetrating mind he/she suffered from Hamlet-like indecision and weakness of will. The Hamlet-like psychology inspired the creation of Józef Korzeniowski’s plays: Aniela (1826) and Mnich [Monk, 1830], and especially Karpaccy górale [Carpathian Highlanders, 1843] where one of the main characters, mentally disturbed Praxed, finds her death Ophelia-like, in the currents of the Czeremosz.14

Also in the Romantic period, in 1875, the first full edition of all Shakespeare’s works in Polish translation was published, the Complete Works [Dzieła Wszystkie] [fig.3]

. Józef Ignacy Kraszewski (1812-1887), the general editor-in-chief, supervised the literary side of the project which helped Shakespeare become the subject of wider study and critical attention in Poland. As a popular novelist, a journalist and the author of a vast number of books depicting the society of both contemporary and historic Poland, Kraszewski had for many years advocated the cultural necessity of publishing the collected works of Shakespeare. Kraszewski’s edition compiled four plays in Stanisław Koźmian’s translation, thirteen in Józef Paszkowski’s and twenty in Leon Ulrich’s. The Kraszewski Edition was a remarkable success. It went through three additional printings (1894, 1895, and 1896). Its success is not surprising, since many parts of the translations indeed display a genuine and unique beauty. Here and there the terseness and precision of the original have been preserved without marring in any way Shakespeare's poetic splendor. Quite often too, the translators manage to catch the tone of the dialogue admirably, conveying it faithfully by using archaisms. On the whole they preserve Shakespeare’s jests, and render even the bawdy with admirable skill (Helsztyński, 1964: 242-8). Each of the plays was preceded by a short introduction that also constituted a survey of the latest Western European achievements in Shakespeare criticism. Besides, the edition supplied Polish readers with copious annotations and it was decorated with woodcuts by Henry Courtney Selous (1811-1890).15

The Kraszewski edition firmly established Shakespeare within Polish culture. Although the translations are not of an even quality, they have been regarded as models by the generations that followed, while Shakespeare’s phrases and metaphors, as used in these translations, became an inseparable part of the Polish cultural heritage.

|

| [fig.3] |

|---|

Initiated and shaped in the Romantic period, the Polish cultural appropriation of the play followed two closely interrelated forms: Hamlet, the play, was wielded as a tool in a bitter social and political commentary, often as a metaphor, while the character, with all his eschatological and metaphysical discourse, became identified with Polish spiritual, artistic and intellectual life. The latter, sometimes called a Hamlet-like psychology or hamletizing, functioned as a mirror reflecting Polish moral paralysis in critical moments of political decision-making. It is not surprising then that in 1964 Jan Kott, who analyzed Hamlet from a Polish perspective, succinctly labeled it “a sponge [...] [which] immediately absorbs all the problems of our time” (Kott 1965: 87).

The political interpretation of Hamlet was probably one of the reasons why it was not staged, or seldom staged, in Poland in the first half of the nineteenth century, yet the general interest in its problematics was, nevertheless, alive. In 1894 Władysław Matlakowski, an eminent Warsaw surgeon, issued an eight-hundred page bilingual volume William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Prince of Danemark, edited and translated, with introduction, notes and supplements. Matlakowski wrote the monograph because of his special relation to Shakespeare:

When, living in a hospital, and awakened late at night to attend a hemorrhaging patient I was returning to my room with my ears full of wheezing, groaning, coughing and grunting, with my eyes blinded with ruby blood gushing from an aorta at a snow like linen, when my eyes were filled with a shining, flaming gaze of a poor patient whose spirit was leaving him together with his blood, when I could hear the voice full of misery from the chapel fill, where the poor people were singing Byzantine Kyrie—or Rorate coeli, I found consolation in the old Englishman. (1894: cdxvi)

An “Introduction” of four hundred pages opens the monograph. It presents the information about controversies over Shakespeare’s text, the oldest publications of Hamlet and world criticism of the play. Matlakowski used in his world criticism section the works cited in the New Variorum Shakespeare Edition of the play by Horace Howard Furness (1877, Vols. 1–2), which he enlarged with various other critical opinions that appeared between 1877 and 1894. Their texts in his own translation are evaluated critically, and in their context Matlakowski gives his interpretation of Hamlet, locating the play in the world canon of literature and stressing its social significance. The remaining pages of the monograph present Matlakowski’s prose translation of the play side by side with the original in English, with very extensive and thorough lexical, grammatical and explanatory footnotes and explications of the translated text.

Though Matlakowski’s translation “does not possess at present any scholarly or literary value because it is too literal and because it demonstrates in many places old-fashioned interpretations of the text” (Chwalewik 1969: 72), it constitutes an important contribution to Polish appropriation of Shakespeare at the end of the nineteenth century. His book was one of the first comprehensive Hamlet studies in Poland. Though over decades many scholars and literary critics have expressed their devastating criticism of Matlakowski’s work (Chwalewik 1969: 73), it had a crucial value for Modern Poland (1891-1918). For the first time in Polish criticism Hamlet was presented as an artist of noble and stately appearance and behavior, able to carry out difficult objectives, but only if they are morally impeccable.

Some attempts appeared to meld the play completely with Polish culture, which produced instances of its direct polonizing, especially in its translations. For example, Krystyn Ostrowski (1811–1882), a writer and translator, gave Polonius a Polish genealogy. Presented as a Polish nobleman captured by Old Hamlet during his war with Poland, Ostrowski’s Polonius was conscious of his tendency to prattle, and he explained this vice as God’s punishment for his sins. Polonius’s national origin located his children—Laertes and Ophelia—in a different context. When after his death Hamlet learned about Polish patriotism and the Poles’ readiness to sacrifice their own lives for the country’s independence, Ostrowski’s Prince exclaimed: “What a special nation! I judged Ophelia’s father wrongly I wish I could be a Pole.” In addition, Laertes initially rejected Claudius’s instigation to use poison during his duel with Hamlet. Such treachery violated the Polish concept of a nobleman’s honor. He changed his decision only after the news of Ophelia’s tragic death. Laertes addressed his sister: “You poor Polish woman, you Ophelia, dear!” and later exclaimed: “My father was Polish” (Tarnawski 1914: 107). Though Ostrowski’s translation was published, its text was heavily censored by the Russian authorities; all the Polish accents were removed for the premiere of Ostrowski’s work in one of the Warsaw theaters in 1871.

Similarly, in his Studium o Hamlecie [Study of Hamlet, 1904] Stanisław Wyspiański (1869-1907), an eminent Polish painter, poet, dramatist, literature and theater critic of the Neo-Romantic period, also introduced a bit of Polish flavor and suggested that the Danish Prince's story could have taken place at the Wawel Castle in Cracow:

You can see him: walking with a book in his hand in the upper gallery of the Jagiellonian palace. You can see him: about midnight going to the guards, where his friend Horatio is waiting for him on the terraces of the Wawel castle near Lubranka, in the vicinity of the Casimier part of the castle, and there the Ghost appears! (1961: 14)16

Wyspiański’s work is usually regarded as the culmination of the Polish appropriation of Shakespeare at that time. He considered himself a heir of Shakespeare while his Hamlet was “one of the first attempts of theatrical exegesis of Shakespeare’s text in Europe” (Gibińska et al. 2003: 51).17

His Studium o Hamlecie not only interprets the text of the play, but also directs its imaginary performance, gives fragments of its translation, supplies illustrations of its characters, and—most of all—locates Hamlet in the Polish political, social and cultural contexts. Yet, it is also Wyspiański’s thinking about theater, a search for its essence, a vision of ideal theater which serves to “hold up a mirror to nature.” Thus, it is an actor who is the main protagonist, not Hamlet. Indeed, the whole work was dedicated to “Polish actors.” For Stanisław Brzozowski, a Polish political writer and philosopher, theatrical critic who evaluated Wyspiański’s works in terms of their usefulness in the process of national liberation, Wyspiański was a “master of the truth.” Though Wyspiański found his artistic inspiration in some other Shakespeare’s works (Macbeth, Richard III and The Tempest), it was his interpretation of Hamlet that laid a foundation supporting Polish interpretations of the play for decades (Miodońska-Brookes, 1997).

Since Wyspiański’s interpretation of the play, Hamlet has indeed become “the Polish Prince.” The play evolved into an inspiration for theater directors, poets and painters who, placing it against a specific political and cultural background, used it as a tool for national introspection. “Portret Aleksandra Wielopolskiego” [The Portrait of Alexander Wielopolski] painted in 1903 by Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929) is usually referred to as the “Polish Hamlet” [fig.4]

. Wiesław Juszczak says that “we have not got here ‘a’ man in a background, which may represent nature ‘in general,’ but a Pole against the background of Poland” (Juszczak 73- 4). Indeed, this is the only painting by Malczewski that refers to Polish history so directly. The subject of the painting, Alexander Wielopolski, was a conservative, pro-Russian Polish aristocrat. Although he wanted to win more liberties for Poland, put in place a Polish school system and local government, he accepted Russian rule over Poland and acted against the Polish national movement. The painting symbolizes Wielopolski’s dilemma: serve the Russian government or try to save the nation by staging one more uprising.

|

| [fig.4] |

|---|

Though the political situation in Poland did not improve in the second half of the nineteenth century and in spite of the severe censorship of that time, Shakespeare’s plays were staged, providing “allusions to such burning issues as public morality, power, cruelty, justice, and attitudes to a government elected with the consent of the people and to a government self-imposed by the usurpers of power” (Csato, 1960: 3). It was indeed the beginning of the well-known “Shakespeare of allusions and metaphors,” which dominated Polish theatrical life up to 1989.18

Additionally, the turn of the nineteenth century is the time when star system started to emerge in Polish Shakespearean theater. Many outstanding Polish stars played in Shakespeare plays and often built their fame on Hamlet. Wincenty Rapacki (1840-1924), whose fame resulted mainly from his “faithful, photographic representation of reality upon the stage” (Got 1965: 79-80), was later in his career greatly valued for his rendition of Hamlet as a dreamer and poet, who suffers from a psychological breakdown. Similarly, Bolesław Ladnowski also built his fame in the role of Hamlet, among others. Helena Modrzejewska (1840-1909), internationally known as Modjewska, was the female partner of Jan Królikowski (1820-1886), Ladnowski and Bolesław Leszczyński [fig.5]

. The critics usually classify her artistic style as a highly developed version of Romantic Realism flavored with a classic sense of beauty and harmony (Żurowski 2001: 132-40).

|

| [fig.5] |

|---|

The Inter-War Period (1919-1939), apart from new editions of Shakespeare's plays published with extended introductions written by eminent Polish academics,19

also produced many outstanding Hamlet roles. Józef Rybicki was one of the most lyrical Romeos and Hamlets. Generally regarded as the most eminent female performer of that period, Stanisława Wysocka (1877-1941) was the first Polish female actor who played Hamlet. Like many other outstanding male players at that time, Wysocka portrayed the Danish prince as a strong person, consistent and seldom wavering in his actions (Komorowski 2002: 190-2). In 1989 Teresa Budzisz-Krzyżanowska, selected by Wajda as his Hamlet, successfully ventured to follow Wysocka’s example (in Hamlet IV, discussed below).

The years of the Second World War and the Nazi occupation 1939-1945 brought a total destruction of Polish cultural life. Theaters and actors, writers and scholars faced the same tragic risk of annihilation. Theaters ceased to exist while many actors and writers were sent to concentration camps, and any formal publications of literary study or scholarly papers seemed unthinkable. It is possible that during World War II there were, however, secret productions of Shakespeare's plays. Since they could not be staged in institutional theater settings, but only in clandestine informal meetings, very few documents of these activities have been found so far. Marek Edelman, the last living leader of the Warsaw ghetto uprising in 1943, recalled briefly in one of his interviews that “theatrical performances took place [there]. Since Shakespeare was forbidden, Hamlet was staged then under the title Duński książe. Dramat przejrzany i poprawiony przez Dawida Rubinsztajna [The Danish Prince: The Drama Surveyed and Corrected by David Rubinsztajn]” (qtd. Assuntino and Goldkorn 1999: 38).

The comedy To Be or Not to Be directed by Ernst Lubitsch and released in 1942 (remade in 1983 by Mel Brooks) is an interesting but quite controversial example of appropriating Hamlet to the Polish context of the 1940s. The story is set in Warsaw at the beginning of World War II. A group of actors from the Polski Theater stage Hamlet which becomes an alternative to their previous performance ridiculing the Nazi regime in Germany. The film initially focuses on an affair between the actress playing Ophelia and an admirer from the audience, who receives as a cue to go backstage and meet with the actress the “To be or not to be” soliloquy, but then shifts to a complex spy story. When the war breaks out, a secret lovers’ code: “To be or not to be” becomes a message that takes on national implications, while the messenger turns out to be a Nazi spy. Using their acting skills, dressed up as German officials and mocking the Nazis, the theater group tries to protect the Polish resistance movement. Made in America, just after it joined the war, by a German-born director of Jewish descent, the film has been often criticized as anti-Polish, or at least making fun of Poles. Apart from the fact that during World War II theatres in Poland were closed, there were other instances that distorted reality and were later viewed as offensive by those who survived the war. Thus, in Poland Lubitsch’s satire appeared nearly twenty years later and with little success. The film was considered too provocative, while its comic convention inappropriately presented life and struggle under Nazi occupation.

The post-World War II period turned into a second “Golden Age” for Hamlet in Polish culture. The second most popular Shakepseare play (after Midsummer Night’s Dream), it was staged more than fifty times, and the number of its revivals intensified at times of political unrest: in 1956, 1968, 1970 and 1981. In the majority of these productions, the play was used as a commentary upon the Polish political situation (Fik 1993: 232-43). The 1956 Hamlet directed by Roman Zawistowski and staged in Teatr Stary in Cracow is usually referred to as “The Hamlet after the Twentieth Congress of the Soviet Communist Party,” the title of Kott’s review of the performance. Performed during the events of the October 1956, the year of transition and destalinization,20

it was a drama of political crime and the police state, a drama of a coup d’etat, a drama of State madness.

For Kott, the Hamlet of 1956 is “acute and clear, tense and rapacious, contemporary and consistent, limited to one cause. It is a political drama entirely and exclusively” (1965: 82). From the study of his Shakespeare Our Contemporary, it becomes clear that his Hamlet focuses on investigations, traps, fear, on the drama of—and only of—political crime (1965: 84). The Hamlet of Polish October is a “rebellious ideologist” (1965: 91) who cannot escape politics. Kott had no sympathy, as he admitted, for all other Hamlets: moralist, intellectual or philosopher (1965: 84-5). His Hamlet is entirely political, while the play is a drama of “imposed situations” (1965: 90) such as the duty to fight for patriotism and national liberation. This politicizing of Shakespeare, placing him exclusively in the Polish context, was what made Kott’s intellectual concept appear subjective and provocative. Yet, though often criticized, Kott did show that Hamlet in totalitarian Poland was indeed Hamlet that absorbed its time—the time when “in the Elsinore Stalin’s crimes were publicized” (1965: 9).21

On the other hand, the prevailing political hegemony sometimes used the play for subverting the most radically progressive ideas. The myth of Hamlet as the symbol of the Polish intelligentsia was ridiculed and derided for political reasons many times in post-war Polish history. Konstanty Idelfons Gałczyński wrote three of his miniatures of the Theater “Green Goose” to disgrace this Polish Romantic myth.22

The third one, “Hamlet i kelnerka” [Hamlet and A Waitress], was a harsh commentary on a dangerous political reality. The restless Polish intelligentsia were an object of a severe persecution in the name of Stalinist law and order at the time when in 1948 Gałczyński’s Prince was dying of “lack of decision and twisting of the bowels at the sharp bend of history,” and one of the characters was writing on his coffin “Hamlet idiota” [Hamlet: an Idiot] (Gałczyński 1968: 56).

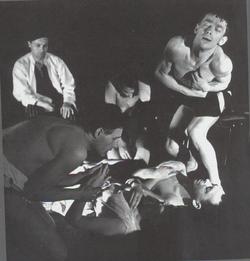

The myth of Hamlet as the symbol of the Polish intelligentsia and the reality of Stalinist Poland is present also in Jerzy Grotowski’s production Studium o Hamlecie [Study of Hamlet] made in his Teatr 13 Rzędów [the Theater of Thirteen Rows] in Opole [fig. 6, 7, 8].23

Grotowski’s Hamlet, staged during the period of the group’s extensive “research and experiment” (1964), became a history about his generation, the most political of all his productions. Wilhelm Mach considered it “very contemporary and very Polish,” while Elżbieta Morawiec—a “precise prefiguration of March 1968,” when Polish authorities tried to turn the working class against Jews and the intelligentsia (Wójtowicz 2004: 119-20). For Eugenio Barba it radiated with “political rebellion,” irritating Polish authorities (2001: 107). Zygmunt Molik (playing Hamlet) stated that Grotowski made Hamlet very political, too political to keep on stage: “Hamlet was a Jew, while the court was presented with direct allusions to the current authorities. This was a clear interpretation, impossible to defend against censorship and the authorities” (qtd. Wójtowicz 2004: 119).

|

|

|

| [fig.6] | [fig.7] | [fig.8] |

|---|

Grotowski used fragments of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, much shortened and rearranged, and Wyspiański’s comments on Hamlet to produce a story about the conflict between individual and society, between intelligentsia and proletarian mob, about Polish working class, “peasants,” and a Polish intellectual of Jewish origin—Hamlet. The story was set in a suburban pub where drunken clientele decided to stage Hamlet, where among drinks being served and barman’s comments on how to play, the major question arose: “who is Hamlet, who are others?” (Wójtowicz 2004: 125). Actually Hamlet was one of the pub’s customers, sitting apart from the others; he was a stranger, different in terms of his clothes and behavior, he was rather silent and slow, wearing glasses and speaking with a Jewish accent. His Jewish origins were an object of mockery, emphasizing the gap between him and the rest of the group. Barba writes about Hamlet that

he is different, others are normal. He thinks, others live. [...] Hamlet is the “Jew” in the community, however we understand the sense of the word: an ideological, religious, social, aesthetic, moral, sexual “Jew.” He is different and thus constitutes a risk. Each group must have its “Jew” [...] to strengthen its own self esteem. (2001: 103)

Grotowski’s Hamlet opposed society:

he did not rebel, only tried to understand, recognize. And he lived in the world of different values than others. He tried to join the action. Without result. Just like peasants tried vainly to stage Hamlet in the pub. And this is how the situation looks like till the end, till the last scene. (Wójtowicz 2004: 132)

Typical of Grotowski’s theater, his Hamlet was experimental, a performance about the birth of performance and, in fact, a workshop, a rehearsal open to the public (Flaszen 1992: 170, 167-8). The performance space was empty and black, accommodating only actors and audience, the scenes were concise and characters clearly defined. The sense of the words was not so important—the audience was expected to know and remember the text—while Grotowski played with tension and emotions, focusing on acting and bodily expressions. In this way Grotowski dealt with major problems of the modern world as a whole: the individual versus society, the bestiality of human nature and alienation; but he also commented on the contemporary situation of his particular society and nation.

In spite of repressive restrictions against Polish intelligentsia, the Hamlet attitude and hamletizing can be found in various texts not only dramatic, but also in poetry, grotesques, and in post-war Polish novels and essays. As he himself admitted, Witold Gombrowicz wrote his play Ślub [Wedding, 1953] on the basis of Hamlet. Permeated with dramatic situations and motifs taken from Shakespeare's model, his drama becomes a philosophical meditation on the crisis of value. Sławomir Mrożek’s play Tango, often called “The Hamlet of The Polish People's Republic” (1964), is also full of interpretive analogies to Shakespeare’s model. It is a play about dictatorship, violence, Stalinism, conformism as well as a sneer at intellectualizing about Hamlet.

The late twentieth century witnessed the “revenge” of Fortinbras who, ignored in the first Polish presentation of the play, came back to monopolize the entire dramatic space. The Polish interest in Fortinbras is probably conditioned by its history. Limon observes that under the Communist regime in the stagings of Shakespeare’s Hamlet

the scene in which Hamlet converses with a captain of the Norwegian army that is marching against Poland (4.4.9-20), often cut from productions elsewhere, has generally been retained in Poland, where this depiction of a foreign military threat has often been crucial for political interpretations of the play. (2001: 149)

The significance of this episodic character increased in the Polish interpretation of the play to the extent that in many theatrical renderings he was either treated as a symmetrical figure to Hamlet, or in many alternative versions of the play, he became a dominant figure in the action.

In Wariacje szekspirowskie w powojennnym dramacie europejskim [Variations on Shakespeare in Post World War II European Drama], Małgorzata Sugiera demonstrates that unlike Kott the authors of the current adaptations “do not even attempt to convince their theatergoers that Hamlet is a contemporary play.” Both Jerzy Żurek in his Po Hamlecie [After Hamlet, 1981], and Janusz Głowacki in his Fortinbras sie upił [Fortinbras Gets Drunk, 1990] “doubt the contemporary adequacy of the Elizabethan dramatist's work as a philosophical universalization of history. [...] New visions of the world, new existential experiences require a new dramatic form” (Sugiera 1997: 42-3). Kott was, nevertheless, aware of new visions of the world and transformations of directors’ approach to the play, and did perceive their “contemporaneity.” Commenting on the changes taking place in theater of the 1980s, he noted that the “Ghost and Fortinbras seem to be more obtrusively the signs of history. And not only of Elsinore. History that was and that may come again” (1999: 254).

Jerzy Żurek’s work presents the fate of Denmark after Hamlet's death, when the rule of Fortinbras and his governor Lizon proves to be a ruthless political game. He shows Fortinbras, initially an idealist, slowly becoming influenced by Lizon, a sober realist and political pragmatist. The ending of the play, which reflects the ending of Shakespeare's original, makes the audience assume the role of Horatio. Only the theatergoers know what really has happened. Denmark’s future under Fortinbras’s rule looks grim, since he has become another ruthless representative of the Great Mechanism of Power. The action of the play, located in Norway, runs simultaneously with the action of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. It begins with the news that a specially trained secret agent has been sent to Denmark to “enact” the role of Hamlet's father, and it ends with Fortinbras’s peaceful exposition over the dead bodies of Claudius, Gertrude, Laertes and Hamlet. The mechanisms of politics become seemingly absurd in this play, though in reality the absurdity becomes a horrifying commentary on the immortality of brutal political life and institutions.

Assuming that Shakespeare’s vision of the world is rather outdated, Głowacki also approached Hamlet from the point of view of Fortinbras. He started writing his pastiche of Shakespeare, Fortynbras się upił [Fortinbras Gets Drunk], in Poland just before the marshal law in 1981, but finished it in New York in 1983. It was published in English in the collection Hunting Cockroaches and Other Plays (1990). He represented Norway as a totalitarian superpower, ruled by the minister of foreign affairs and secret service agents in the name of the king who has been dead for a few years, though nobody knew about that. Denmark, on the other hand, was a weak, little country, subordinate to Norway, its spies and informers. The political allusions of this tragicomedy were immediate and obvious in Poland. Yet, staged in USA, London, Sarajevo and Moscow, the play became—perhaps even against the playwright’s intentions—a more universal macabre retelling of Hamlet which under its grotesque cover hides various urgent social and political tensions.

The character of Fortinbras has also inspired Polish poets, as Marta Gibińska demonstrates in her monograph Polish Poets Read Shakespeare. Refashioning of the Tradition (1999). “Tren Fortynbrasa” [Elegy of Fortinbras] was written in elegant blank verse by Zygmunt Herbert, one of the most significant Polish twentieth century poets, and presents Fortinbras’s soliloquy over Hamlet’s dead body. The poet draws a psychological portrait of Hamlet through Fortinbras’s eyes. Fortinbras believes that Hamlet was a melancholic loser, unable to rule the kingdom or find his own place in the world, who

... believed in crystal notions not in human clayAlways twitching as if asleep you hunted chimerasWolfishly you crunched the air only to vomitYou knew no human thing you did not know even how to breathe.

Although motivated by the desire of power, Fortinbras wants to act practically and rationally, wants to deal with rational problems; he says: “Adieu prince I have tasks a sewer project And a decree on prostitutes and beggars” so that what he “shall leave will not be worth a tragedy” (Herbert 1968). In her essay “Life After Life—Hamlet Behind the Iron Curtain,” Marta Wiszniowska states that:

Though the future belongs to the living, Fortinbras accuses Hamlet of having chosen an easy way out, subsequently making unfair claims to glory and fame [...]. The speaker is sorry for himself and the attributes of power have no appeal for him [...] Fortinbras will do the dirty job, meaningless for posterity, while Hamlet's fame will never fade.

The poem, as Wiszniowska commented, “bids farewell to the heroic, romantic Hamlet, so prominent to the Polish tradition of reading the play's message.” In Herbert's poem “Hamlet is a star” still “shining,” but “distant, cold, and unattainable.”24

Similarly, Gibińska noted that becoming “the political space of Poland, [...] of the changes the memorable year 1956 seemed to bring,” Herbert’s poem became an instance of his defiance of the Polish tradition of reading Hamlet, not by rejecting it as an inadequate and empty idealism [...], but by shaking the narrow-minded vision it offered” (1998: 164). Herbert, who belongs to the generation of the post-war poets—the “survivors”—experienced the tragedy of war, witnessed the reality of totalitarianism and became disillusioned about human nature. In spite of despair, however, he clung to this hope in righteousness and honesty.

Unlike Herbert, Tadeusz Różewicz, another survivor of World War II, perceives existence as the struggle against nothingness. He, Gibińska believes, also “cancels the continuity of the Polish Hamlet myth,” moving from romantic “emotional idealism” to “moral and intellectual reflection” (1998: 158, 165). Różewicz thinks the Polish Hamlet myth is no longer adequate in the cruel empty world entirely devoid of moral values. His poem “Rozmowa z księciem” [Conversation with a Prince, 1960] is an attempt to re-read Hamlet and Shakespeare, while debating traditional ideals, confronting civilization “after Auschwitz,” human cruelty, destruction of social bonds and views. Różewicz discusses with Hamlet the values of the post-war world; his conversation is, as Gibińska stresses, “the beginning of a new tradition of reading Shakespeare in the post-war poetry: the tradition of appropriation by questioning” (1998: 161).

New political concerns, however, redirected the attention back to the everyday concerns. Under the Communist regime Shakespeare was seen as a perfect medium for the discourse of political significance, and theater—as a place to stir national conscience. Since attendance at politicized dramas carried the air of a meaningful gesture of defiance against Communist totalitarianism, the productions of Shakespeare’s plays in the convention of “political allusions and metaphors” attracted large crowds of people (Kujawińska Courtney 2006b). It should be stressed, however, that very often the subjective reading of the plays presented a need to vent their frustration, rather than the directors’ interpretation as reflected in a given production. For example the imposition of martial law in December 13, 1981 rapidly reactivated the presence of political allusions and metaphors. Andrzej Wajda’s Hamlet staged in November 28, 1981, in the Theater Stary in Cracow was originally produced as an ambitious performance without any political undertones. In one of the programs’ pictures Wajda is seen contemplating his own hand showing the “V” sign, but there were no clear allusions to the Polish situation [fig.9]

. The “political” aura arose unexpectedly after the imposition of martial law in December 13. The audience found allusions to the external situation: students’ strikes, imprisonment of “Solidarity” members and the violence of the police and army. The critics and audience could recognize that Fortinbras was dressed and behaved like a member of the Polish Riot Squad, hated after December 13. Many fragments of the play, such as “Forgive me this my virtue. For in the fatness of these pursy times. Virtues itself of vice must pardon beg” (4.4. 152-4), spoken directly to the public, evoked standing ovation.

|

| [fig.9] |

|---|

For centuries various motifs taken from Shakespeare’s works appeared in Polish pictorial arts. Hamlet has most frequently served as an inspiration for Polish painters, who demonstrated their interpretation of this play in their works (cf. Cyprian Kamil Norwid, Władysław Czachurski, or Wlastimil Hofman).25

In a particular political context of the Communist regime Polish Hamlet was created by Jerzy Duda-Gracz (1941-2001), a professor of the European Academy of Art in Warsaw, an artist suffering from—as he often repeated—“a wonderfully incurable illness”—Poland. His “Hamlet Polny” [The Field Hamlet, 1977] [fig.10]

presents Hamlet dressed in some elements of Polish folk costume, meditating in a field of cabbages. The painting, grotesque and tragic, mixes and distorts Polish romantic and modernist traditions, transplanting the tragic hero into provincial scenery. It can be perceived as a critical and derisive commentary on communist Poland as well as the observation on “Polish mentality, Polish pride and provincialism.”

|

| [fig.10] |

|---|

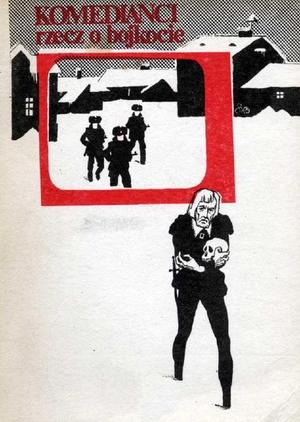

The imposition of martial law evoked an unparalleled interest in the role of the actors in Hamlet. In the 1983 Warsaw performance, the actors seemed the only honest people in the world of brutal corruption and bloody terrorism. Since many Polish actors at that time refused to cooperate in any of the mass-media, they risked poverty and political persecution. On the cover of Komedianci: Rzecz o bojkocie [Comedians: The Issue of Boycott, 1989], a compilation of stories about the Polish actors who joined the boycott, Hamlet with his skull is presented as being taken from a television studio under military guard [fig.11]

. In Janusz Kijowski's film Stan strachu [The State of Fear, 1989], the dilemma of the main character as an actor was to decide whether he was to play or not to play Hamlet in December 1981—the December of the imposition of martial law. His dilemma added a metaphorical dimension to the Polish people's situation: caught in the web of political machinations, they had then to make significant moral choices.26

|

| [fig.11] |

|---|

In 1989, when Poland became a democratic country, Andrzej Wajda produced his fourth staging of Hamlet called Hamlet IV.27

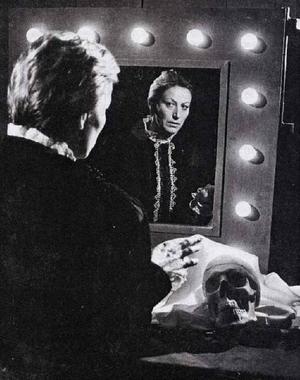

The action was presented in two locations: in the dressing room and on the theatrical stage. Audience gathered in the dressing room could see the stage where the rest of the action—the action in which Hamlet was not personally involved, was taking place. Budzisz-Krzyżanowska played both Hamlet and the actor who was to play that part [fig.12]

. Urszula Bielous noted that it was very difficult to pinpoint when the performer was becoming the character in the play (1989: 10). Walaszek remarked that “[t]he audience witnessed her struggling with the part [...]. Thus the creative work of the actor [...] became one with the stage-life of Hamlet” (1998: 117). In Budzisz-Krzyżanowska’s interpretation Hamlet was a reflexive and calm individual—despite all his pain and aggression—as if in her performance, the actor were writing an essay on human nature. In other words, Budzisz-Krzyżanowska was not a woman dressed up as a man, but an incarnation of Hamlet’s predicament, which is not gender specific (Bielous 1989: 10). The performance was intriguing in many ways; apart from commenting on the nature and functions of theater as such, it drew attention to a more current and context-specific problems, namely, the changing social and political situation in the country and the role of theater in this new Polish reality of the late 1980s.

|

| [fig.12] |

|---|

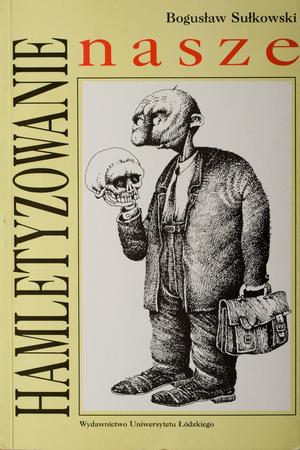

In Hamletyzowanie nasze: Socjologia sztuki, polityki i codzienności [Our Hamletizing: Sociology of Art, Politics and Daily Life, 1993], [fig.20]

an empirical sociological study of the response to Hamlet in the years between the suspension of the martial law (1984) and the introduction of democratic system (1989), Bogusław Sułkowski caught, one hopes, the last moment of popular Polish “hamletizing” as a reaction to a specific political predicament. Almost all respondents to his questionnaires saw the play in their own personal terms: they talked more about themselves than about the work of art. For decades Polish intellectuals assumed the myth of Hamlet as a certain way of behavior in the conditions of censored discourse. In their appropriation the tragedy emerged as a play on the tragic nature of individual fate, chaotically caught and destroyed by the crazy grindstones of history. Perceiving themselves as Hamlets, the Polish public sympathized with his predicament, understanding it in terms of humanity’s fight against history. They found sarcasm in his reaction towards history and they identified with his questioning the possibility of finding any law regulating historical processes. Saturated with nihilism, the Polish viewers of the play expressed their empathy with the Prince, finding similarity between him and themselves as objects of a ruthless political manipulation, who often had to adopt unconsciously the rules of their oppressor’s immoral game.

|

| [fig.20] |

|---|

With the changing of the political system (1989), the Polish theaters became deprived of their two powerful allusions: dreams for independence of Poland and anti-totalitarian impulses. Zbigniew Majchrowski, for example, deftly observed that Shakespeare’s “Denmark is a prison” could no longer be understood by a Polish audience as a veiled shout “let out all political prisoners” or “let Poland be at last Polish.” “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” could no longer be treated as a direct criticism against the Communist regime's corruption and political inadequacy (1993: 24-5). The new system meant the end of the specialty of the Polish stage: the end of the theater of political metaphor, the end of political Shakespeare, the end of political Hamlet.

Since for many decades the theaters followed the same artistic technique–the politicization of Shakespeare–they face now the same problems: a lack of a sense of form and an inability to create theater from the text alone. In a broader sense, one may say that the Polish stage tradition does not possess the language and the conventions of expression, which are crucial for staging Shakespeare, and which must be developed gradually. Yet there is no dearth of productions of Shakespeare’s plays in recent years. They are produced by theaters of all ranks as well as on television. The titles of the plays which once dominated Polish stage have, however, changed.28

His tragedies are less often produced, as if their problematics, bloody struggles for power, the rule of tyrants and the ruthless Grand Mechanism of history might undermine the relatively young democratic system of Poland (Baniewicz 2000). To escape the political implications of tragedies some directors have looked for unusual interpretations.

Though the new generation of theater performers, directors, and stage designers work in a different ideological milieu, the Polish theatrical heritage still affects their work, even when they maintain that they completely reject it.29

Agata Adamiecka believes that a certain continuation of tradition can be detected in the highly aesthetic productions directed by Maciej Prus and Krzysztof Warlikowski, who, “suspicious towards states of consciousness [...] attempt to reveal paradoxes of human existence in the world” (2000: 74-5).

Warlikowski received many Polish and international awards for his artistic achievements, starting in 1999 with his challenging staging of Hamlet in the Warsaw Rozmaitości Theater. Warlikowski seemed to ignore political undertones and allusions, so important on the Polish stage in the past, and focused on the play as a family story. He presented Hamlet as a drama of existence and the main hero as psychologically dependent on his mother, in fact overwhelmed by his childish desire to monopolize her love. Their intimate relations were fully revealed in a scene (3.4), in which the prince rushed naked into her chamber. In addition, Warlikowski’s Hamlet was a homosexual, playing sexual games with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, whose parts were performed by women. In this production of the play the boundaries between the sexes collapsed. According to one critic, the director turned to transgression to reveal his characters' ongoing search for identity. Warlikowski “presented classical figures as contemporary people—great individuals, unpredictable and driven by basic human instinct” (Pawłowski 2003: 45). Though Warlikowski’s defenders stressed his originality, the production earned him the name of a “scandalizer.” He was accused of “bad taste” and “moral impropriety,” an accusation which, according to his admirers, proves how “superficial is still the reception of contemporary art in Poland” (Gruszczyński 2003: 108).

In 2003 Maciej Prus staged Hamlet in Teatr Nowy in Łódź. He took the performance over after its director, Kazimierz Dejmek, died a month before the first night.30

As the actors testify, Dejmek focused on Hamlet as if he wanted to make an autobiographical story, a play about a young yet mature boy, uncompromising, idealistic—a lonely individual with a great sense of humor (Pawłowski, “Reszta jest milczeniem,” <http://www.teatry.art.pl/!recenzje/hamlet_dej/resztaj.htm>, access date: 15 May 2008) [fig.13]

. At the same time, he put great emphasis on the motif of theater within theater, entirely eliminated Fortinbras as well as any references to body, passion, flirtation, eroticism and homosexuality. Pawłowski suggested that this negation of bodily elements and biology could be interpreted as the director’s comment on the contemporary world, a reaction to and a protest against the body cult in modern culture, especially in theater. In this respect, Dejmek’s Hamlet entirely opposes Warlikowski’s production which rather focuses on and exposes these aspects (Pawłowski, “Nie o to szło,” <http://www.teatry.art.pl/!recenzje/hamlet_dej/nieo.htm>, access date: 15 May 2008). The production finished with the act 4, the last act that the actors had discussed and rehearsed with Dejmek. The performance, although criticized for being a bit outdated and “flat,” deprived of deeper and more contemporary meaning, was applauded, perhaps because its reception was very much influenced by the death of its director.

|

| [fig.13] |

|---|

Nonetheless, the political past has not disappeared entirely from most modern Polish theater; but it is often mixed with more current themes and events. In 2004 a young director Jan Klata (b.1973), who describes himself as a “designer of interpersonal catastrophes,” decided to stage Hamlet, under the title H., in a space loaded with meanings and allusions—in the Shipyard in Gdańsk. At that time the Shipyard was an empty and devastated space, but its history of being a socialist production venue known as the Lenin Shipyard, and later the birth place of the Solidarity trade union, was still alive. With the strike of ship builders in 1980, the Shipyard has remained a symbol of rebellion against the communist reality, against lies and tyranny, the symbol of the collapse of communism, enslavement and political paralysis.

The performance took place on two levels of crane hall; the audience, who followed the actors, moving through the gloomy nooks and crannies of the hall, saw the body of Ophelia picked out from the harbor dock, and they searched for Polonius’s murderer in dark corridors of the shipyard. Although the performance was criticized for being deprived of meaningful expression, as if “lost” in this huge industrial space and requiring too much effort on the part of the audience (who had to listen attentively to actors speaking too quietly or following them through the dark area), it did gain a lot of attention and fame as a bitter comment on Polish reality. Klata himself described the performance as being “about what happened after 1989.” In one of the reviews, Hamlet in the Gdańsk Shipyard was described as demonstrating “present-day Poland, where the governing would prefer to forget about the past, and where a large part of the younger generation feels cheated and rejected, just like Hamlet.” In the same review Hamlet is described as the “most Polish of [all] Hamlets,” a Christian who follows the Decalogue and who has “a prayer book from which H. reads the prayer “Our Father” to Polonius.” The present times and themes are depicted by turbogolf played in the Prologue (a golf club is also Hamlet’s weapon against Polonius), breakdance shows, monologues delivered as if by amateurs attending some sort of a commercial casting, as well as demonstrations of cynicism and decadence by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

It seems that in the modern productions of Hamlet it is the space, interesting and unconventional, that in a way replaces the peculiarity of the Polish political context and the Polish traits assigned to the main character. Apart from Klata’s Hamlet, Łukasz Barczyk’s television theater production of Hamlet (2004) also gained publicity and acclaim owing to the original and unusual venue where it was set [fig. 14, 15, 16].31

|

|

|

| [fig.14] | [fig.15] | [fig.16] |

|---|

Barczyk presented his Hamlet in an ancient salt mine in Wieliczka, near Cracow.32

A space consisting of a great room with rough salt walls, dark passages, labyrinth-like tunnels, and underground lake, created the feeling of claustrophobia, enclosure, encirclement and helplessness:

The lens of [...] the camera makes Wieliczka even more of a labyrinth than Olivier’s Elsinore, more of a prison than Kozintsev’s castle, more of a tomb than Richardson’s Roundhouse Theater, and more menacing than Almereyda’s New York. It renders the salt mine varied and oddly alive. Impressive long shots of the spacious halls (for example, in Claudius's first court address or the Mousetrap scene) give the impression that the mine is a gigantic cave encapsulating the tiny characters. (Cieślak 2006: 49-50)

Perhaps this enclosure and claustrophobia is what made the performance “contemporary,” allowing for modern allusions. There are, however, other dimensions of this contemporary rereading of the play. Barczyk’s Hamlet, in which he cast renowned Polish actors (Janusz Gajos, Grażyna Szapołowska, Zbigniew Zapasiewicz, Jan Frycz), can be viewed as a play about growing up, becoming a man, an individual (Gałązka 2004: 10). It opens meaningfully with the soliloquy “to be, or not to be,” later in the play Hamlet behaves like a child crying hysterically over his father's ashes, while Fortinbras is a handicapped 10-year-old boy (with leg braces) who is “so serious and mature that Hamlet, by comparison, seems nothing more than a snotty-nose kid” (Cieślak 2006: 52).

As Cieślak writes in her essay:

That is exactly what a ‘new millennium’ audience might relate to. The last decades of the past millennium were marked by feminism, gay liberation, the fall of communism, the establishment and development of the European Union, ecumenism, religious wars and terrorism, etc. Such phenomena, all of which have involved the seeking of new identities, be they national, religious, sexual, or political, have shaped the reality of the new millennium. (2006: 53)

In this sense, the production acquired its universal and at the same time very contemporary character. Barczyk avoided direct references to present-day contexts. He used the translation by Józef Paszkowski from the 1860s, and analyzed Hamlet from the perspective of Carl Gustav Jung’s archetypes theory, explaining:

I don’t think that this great Shakespeare’s drama would have to be set in the reality that surrounds us, that the world of advertisements, escort services, poverty, war in Iraq and drugs has to be directly presented in the play written four hundred years ago. I situated the story in a metaphorical setting to focus on what is eternal in this work, on problems that are up-to-date independently of the times in which we live. (qtd. Bończa-Szabłowski, “W Teatrze Telewizji...,” <http://www.teatry.art.pl/!recenzje/hamlet_bar/wteatrze.htm>, access date: 15 May 2008)

Indeed, the Wieliczka salt mine enables such universal interpretation: it provides a rather abstract background, a space undefined in terms of time and space, a space that is “everywhere” and “always.” The abstract setting of the play, its timelessness is also conveyed through the actors’ clothes: traditional and Renaissance in the case of Claudius, Polonius and Laertes, and rather modern in the case of Hamlet (a worn-out leather jacket), Ophelia and Gertrude (modern dresses).

This universality and timelessness is what most modern Polish re-readings of Hamlet seem to aspire to. Political problems and direct allusions characteristic of the Polish context have been exhausted. Theater has turned towards what is universal, if not timeless, to what is common to other countries and nations, to the problems of a globalized world and contemporary global issues. In 2001 Jacek Głomb (stage design) and Krzysztof Kopka (director) presented their Hamlet, książe Danii [Hamlet, Prince of Denmark] as a comment not so much on modern Poland as on the modern world [fig.17]

. Głomb has become known for staging his productions in unconventional spaces: in warehouses, back yards, a closed cinema room, and former barracks of the Russian Army. His Hamlet was also staged outside the theater building, in the ruins of a former community center. The devastated space seems to represent the ruins of civilization, of the modern world in which the characters struggle to survive. The audience, harassed by the actors begging for money, enters their own world of the twenty-first century. It is the cruel world of intrigues, brutality and war, struggle for power and influence, where love does not bring consolation, family does not mean much and power always seems insufficient. The play starts with the funeral of old Hamlet and ends with Horatio putting a crown (made of machine gun cartridge belt) on his head and reciting Fortinbras’s lines. The production itself was also very “modern”—it was very visual, full of fighting, belching fire, blood and frenzied action.

|

| [fig.17] |

|---|

The Hamlet directed by Tomasz Mędrzak and staged in Ochoty Theater, Warsaw, in 2001 [fig.18]

appears to be even more modernized. Although the director used the nineteenth century translation by Józef Paszkowski, the whole performance was to be visually very modern. Hamlet was played by a 21-year old student, actors were wearing modern clothes, and the stage design was reduced to minimum and consisted only of tangled ropes and chains. The music used in the production was composed by Robert Gawliński, the leader of “Wilki”—a very popular rock band from Warsaw, and together with light effects and smoke, contributed to an impression of participating in a rock concert rather than a Shakespearean tragedy. Mędrzak wanted his audience to identify with Hamlet; he explained: “I address this performance to young people. I would like them to see one of their friends in Hamlet—a contemporary boy who is wondering: to be or not to be... should I reach towards my soul, wisdom, culture? Or possessions?” (“Spektakle Archiwalne,” Teatr Ochoty, <http://www.teatrochoty.pl/_repertuararch.asp>, access date: 15 May 2008). The democratic system means, at least at this moment, the disruption of the theater of political metaphors and allusions, the disruption of political Shakespeare and the politicizing of his theater, but it also means an opening for his commercial appropriation, for his absorption by the popular culture, especially in advertising, in free-market economy.33

In a way commercialism has revealed to the Polish people that Shakespeare can “sell things to us.” Since the Communist regime firmly embedded him in the general consciousness as a cultural symbol, which creates structures of meaning traditionally fulfilled by philosophy or religion, Shakespeare has been accepted very easily as the means that effortlessly translates statements from the world of ideas into a form that means something to people: the “ideas” engender a humanly symbolic “exchange-value.”

|

| [fig.18] |

|---|